What “Diversity and Inclusion” Means at Microsoft

How merit is undermined at one of the world's biggest companies

From 2021 to 2022, I worked as a manager in Microsoft’s AI Platform division. I’ve been working in the software industry for over a decade, and while I’ve often encountered some combination of the words “diversity” and “inclusion,” how those words have been translated into culture and policy has varied dramatically over time and between companies. At Microsoft, I became concerned about diversity and inclusion policies that required me to sacrifice what I viewed as the best way to serve the company’s mission, particularly as it affected work prioritization, hiring, and promotions.

Large companies like Microsoft have a major impact on their billions of users. But they also influence other companies’ cultures and policies, since former employees move on to other firms and use what they learned, and some people view things being done at large successful corporations as “best practices.” How these cultural and policy issues manifest themselves at universities has received a lot of attention. My aim in writing this piece is to raise awareness of what’s going on inside one of the world’s most valuable companies.

I’m publishing this article pseudonymously because I fear I would be fired or many companies would in the future refuse to hire me for writing it.

Microsoft classifies its employees by race, gender, and other categories, and aims to increase the shares of employees in preferred groups. This is not a secret. Microsoft has publicly committed to racial equity, including an effort to “double the number of US Black and African American, and Hispanic and Latinx people managers, senior individual contributors, and senior leaders.” The company publishes an annual report on Diversity & Inclusion (hereafter shortened to “D&I”) in which it tracks its progress toward such goals. Some “gains” noted in the 2021 report include:

Amongst US employees, Hispanics increased from 6.5% to 7.0%.

Amongst all employees, women increased from 28.6% to 29.7%.

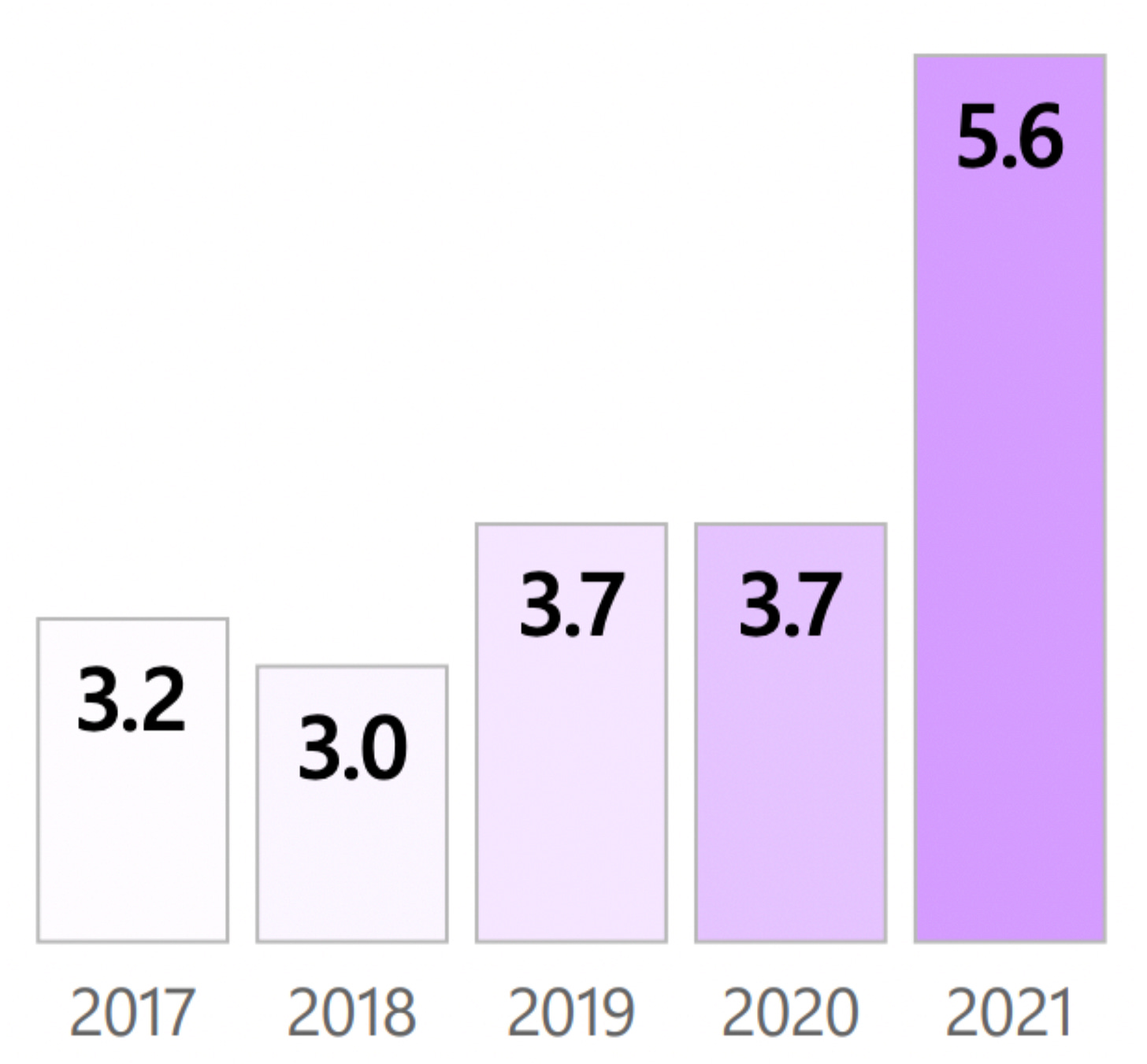

Amongst US executives, Blacks increased from 3.7% to 5.6%.

So how does Microsoft achieve this progress?

D&I Must be a Core Priority of Every Employee

Every Microsoft employee has to complete a “Connect” several times a year. As part of this process they must write out their priorities for the coming months, and how they plan to make progress on them (“critical indicators of success”). This text must be reviewed and approved by the employee’s manager.

You might think that a company that spent time writing a mission statement would ask employees to focus on its mission (Microsoft’s is “to empower every person and every organization on the planet to achieve more”). But every Microsoft employee instead is told that D&I must be a “core priority,” and that they should write about that first, and then “briefly” discuss their own additional priorities. Below is the text shown to employees:

When I initially saw this, I thought I would just write something anodyne and get back to focusing on producing great software for our users. But I soon learned that there was more to Microsoft’s commitment to D&I than making me write some text that was only visible to my manager every few months. I received an email from my corporate vice president (2 hops below the CEO), requiring all managers and employees above a certain level to publicly share our personal D&I plans.

I soon learned that if I wanted to get promoted, visibly announcing my commitment to D&I wasn’t enough. The corporate vice president who sent that email had to approve all promotions within his organization above a certain level, and it was made clear to me that he weighed contributions to D&I very heavily when making those decisions, and that he encouraged lower levels of management to do the same.

To contribute to D&I, people did and were encouraged to do the following:

Hire “diverse” candidates (more on that below).

Promote “diverse” employees (more on that below).

Participate in a “culture club,” which organized speakers, book clubs, and movie showings focusing on topics like allyship and discrimination.

“Diverse” Candidates are Preferred During Hiring and Promotion

An important and challenging part of my job was hiring people at a time when the labor market was tight and our competitors were offering better compensation, remote work policies, and higher levels of prestige (would you rather work at Google on Gmail or at Microsoft on Outlook?). But in addition to all of these challenges, the company also put in place additional constraints in the service of D&I.

As a hiring manager, I was told that for any position to be filled in the United States I had to interview:

At least 1 African-American, black, Hispanic, or Latin candidate, and

At least 1 female candidate.

The slide below mentions a part of the company called “CELA” (Corporate, External, and Legal Affairs), but my impression was that it applied company-wide.

There weren’t any quotas around how many of these “diverse” candidates I had to actually hire, but I was pretty sure my corporate vice president would be more likely to promote people who had hired more of them and thus made his contribution to the annual D&I report look good.

For one position I was trying to fill, dozens of people applied, and most of them seemed qualified based on their resumes, but I spent months waiting for a single person to apply who fulfilled the racial requirement. When no one did, I spent hours trying to find people on LinkedIn who I thought might count as black or Hispanic based on their name or resume. Sadly, during these months I had many very qualified internal candidates applying for the role, but I couldn’t hire them. Unable to hire, my team became a bottleneck that delayed several projects integrating AI into Microsoft products.

You might imagine this policy doesn’t bias the hiring process, since managers are still free to choose who to hire after interviewing the diverse candidates. But because of the number of applicants, most are rejected based on their resumes. Imagine diversity candidates are 1% of the applicants but 15% of those interviewed. This gives those candidates opportunities to do well in interviews that their peers with similar resumes do not get.

In my role as a manager, I recommended employees for promotion. About a week after submitting one set of recommendations, I got an instant message from someone in human resources along the lines of “Hi, did you consider recommending [one of my subordinates] for promotion?” I replied, “I think I’m missing some context, can we discuss this over video?”

During the video call, I was told that HR was reviewing employees from “diverse” groups and making sure they had been considered for promotion. I told HR that I had considered it and I believed my recommendation was correct. HR said “OK, then we don’t need to change anything. I just wanted to check that you had considered them.”

Again, there was no quota, but it seemed clear that promoting this person would have made HR and my corporate vice president happy. At Microsoft, a division is given a fixed promotion budget each year, so promoting one person generally means not promoting another.

Microsoft doesn’t discuss these policies with employees outside of HR and management. In the prompt that the company shows to all employees on its “core priority for diversity & inclusion,” the message is that D&I is about creating a culture “where we do our best work as a result,” and there is no mention of group identities or preferences in hiring and promotion. In this framing, D&I is a means of optimizing how people interact at work, not about changing the company’s demographics or giving better jobs to one group at the expense of another. In contrast, the hiring and promotion policies push away from hiring and rewarding people for contributing to the company’s mission. This is largely hidden from everyone other than managers and HR.

When I began my career, I believed that the systems for determining who got a job or a promotion at a company like Microsoft at least aimed at an ideal of meritocracy. Now I believe Microsoft hires and promotes people partly based on their group identities. Imagine you work under a black executive at Microsoft. Does a graph like this one make you more or less likely to think they got to where they are because of their accomplishments?

I fear that when large companies hire and promote people based on group identities, it discourages individuals from cultivating their abilities and ultimately hurts the corporate mission.

DEI commissars are well paid professional racists. They destroy company culture and in healthcare take resources away from patients. Here is a case study: https://yuribezmenov.substack.com/p/how-to-fire-a-commissar

Very interesting. I'm a partner at the consulting arm of a Big 4 company (also writing using a pseudonym), and it's very similar to what happens in our firm.

We use these D&I metrics in many places, notably % of people in such groups. And while we tout our incredible numbers to the four winds, they're primarily located in support/admin and the lower ranks. Directors and partners, however, are primarily white males.

I agree that diversity in executive ranks would improve our problem-solving capability and our value to our clients. However, we do it precisely as the author writes: tipping the scales of recruiting and promotion so that more diverse people have a better chance.

By themselves, these efforts are not necessarily flawed. They do accelerate the diversity in the firm. The problem is that they have to work alone, with no complementary measures to improve training and retention.

So you get a situation in which, for example:

- We promote more diverse people to partner ranks - still very few, but more than meritocratic evaluation would promote alone;

- Then we leave them to fend for and find clients by themselves;

- By the end of the year, they have done worse than others (not all - some indeed do perform spectacularly! - but many don't);

- Since variable compensation is meritocratic with a mix of seniority and eat-what-you-kill, they tend to get lower bonuses and be perceived as not-quite-up-to-speed;

- Then a significant number either leave for an executive role, having achieved the partner-level stamp in their CVs; or get recruited by a rival firm since hiring bonuses are much more discretionary than end-of-year ones;

- And so, to make up the difference, we have to continue disproportionately promoting diverse directors and also recruiting diverse partners from other firms.

In conclusion, I'm not against giving a better shot at recruiting and promotion to diverse populations. But doing that and only that, with no extra support, no performance improvement or retention efforts, is a big shot in the foot.