General introduction to the series

On the morning of February 24, 2022, as Russian troops marched into Ukraine, the world woke up to find out that it had entered a new era. By ordering the invasion of Ukraine, Vladimir Putin did not just destroy the lives of countless people in Ukraine and Russia, but also shattered what little was left of the hopes born at the end of the Cold War. Between 1989 and 1991, the Berlin Wall had fallen and the Soviet empire in Central and Eastern Europe had disappeared almost overnight, while the Soviet Union itself had followed suit shortly afterward. Almost everywhere in the Eastern bloc, communist leaders were replaced by democrats, who organized competitive elections and launched reforms to transition to a market economy. Even before the Soviet Union disintegrated, the communist leadership had started to democratize their country and had effectively put an end to the Cold War through negotiations with the US and its allies, resulting in vast reductions of armament both nuclear and conventional. For the first time in decades, people did not have to fear a war between NATO and the Warsaw Pact, which unless it was stopped in time could have led to a nuclear exchange and the destruction of modern civilization in both Europe and North America. The future seemed bright and people looked ahead to a new era of peace, democracy and cooperation. Unfortunately, thirty years later, we know that it wasn’t meant to be. This vision of a bright future did not unravel all of a sudden but slowly over many years and the invasion of Ukraine by Russia in 2022, which kicked off the largest war in Europe since WWII, was merely the conclusion of a long process.

Why did this happen? According to the prevailing narrative, the answer to that question is very simple. Unlike Germany or Japan, Russia never truly rejected imperialism and, though after 1991 it was temporarily weakened, it continued to aspire to dominate its neighbors. Out of naivety, and despite being told this repeatedly by Central and Eastern Europeans, the West refused to act forcefully against Moscow’s imperialist tendencies. In particular, after Russia invaded Georgia in 2008, the West did not give up the hope that it could reach some kind of accommodation with Moscow and refused to break off relations with it. Neither the US nor the EU took sanctions against Russia in response to the invasion. Instead, the US launched the so-called “reset” in 2009 to improve relations with Russia, which led to various political and military agreements. Meanwhile, Germany and several other Western European countries continued to build the Nord Stream pipeline under the Baltic Sea in collaboration with Russia, which allowed them to secure a supply of Russian natural gas that bypassed Ukraine and therefore weakened it by reducing its leverage over Russia. Even after Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, in violation of several international treaties it had ratified, the West reacted weakly and only adopted limited sanctions. This emboldened Putin and, when Ukraine refused to obey his diktat by adopting a federal constitution and granting autonomy to Donetsk and Luhansk (where Russia was covertly supporting the separatists against the Ukrainian armed forces), convinced him that he could get away with a full-blown invasion.

In a series of essays, I will argue that although this narrative has now become largely uncontroversial, it’s extremely simplistic and in some respects even gets things backwards. That is not to say, of course, that Russia is not imperialist and that this didn’t play a role in the sequence of events that resulted in the invasion of Ukraine. But there is a lot more to this story and, as I will argue, the deterioration of relations between the West and Russia that made the invasion possible in the first place would not have occurred if the West, not just Russia, had not made several mistakes after the end of the Cold War that needlessly aggravated Moscow. Nor does it mean that, as some people think, the US and its allies deliberately provoked Russia into invading Ukraine. Rather, bad luck and policy mistakes not only in Russia but also in the West and Ukraine conspired to create a perfect storm, which led to the events of 2014 and ultimately to the invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Nobody forced Russia to invade Ukraine, but historical events always have several causes and there is no such thing as a law of conservation of blame, so the fact that Russia bears the bulk of the responsibility for the war doesn’t mean that nobody else is to blame for it. As we shall see, there is an element of Greek tragedy in what happened, as nobody intended their actions to result in that outcome, but that is not to say that it was inevitable. I don’t think it was, but to understand how it could have been avoided, one has to understand how it came about.

The problem is that, in order to understand what happened and how it could perhaps have been avoided, one has to go back all the way to the end of the Cold War and carefully pore over more than thirty years of history, for without this context it’s simply impossible to understand more recent events and one is bound to misinterpret them. This makes it difficult for people who think it’s more complicated than generally understood to make their case effectively, because they have to challenge assumptions that are now deeply entrenched, and this requires launching into long historical explanations that vastly exceed most people’s attention spans. By contrast, proponents of the prevailing view have a narrative that is not only superficially compelling and consistent with people’s prejudices (since it fits the handful of facts they know or think they know about very well), but can be presented very succinctly. As historian Mariana Budjeryn wrote on a related issue, “complicated histories are unpopular, as they do not readily translate into political slogans”.1 Anyone who aspires to challenge this narrative has therefore his work cut out for him, but I shall nevertheless endeavor to do so and ask that you keep an open mind as I present my interpretation of the events I discuss in this work.

In order to challenge the prevailing view, it’s not enough to look at the facts;, the historical analysis has to be informed by clear thinking about morality and foreign policy. As Paul D’Anieri wrote after identifying some normative questions one has to answer to say how the events of 2014 could have been averted:

These are normative questions whose answers depend on further assumptions about the rights of great powers, the inviolability of sovereignty and international law, the boundaries of realpolitik, and so on. How one answers those questions will determine whose claim one believes has greater weight, who should therefore have backed off, and who, in the final analysis, is guilty of not backing off and therefore to blame for the conflict. Even in February 2014, violence could have been avoided as long as each side refrained from shifting to violence. Whether that move to violence should be blamed on protesters in Kyiv, on Yanukovych, or on Russia also falls back on normative assumptions. Thus, rather than history or analysis resolving who is to blame, how one assigns blame tends to shape how one writes or reads the analysis.2

Indeed, it’s not just the historical analysis embedded in the dominant narrative that is simplistic, but also the normative assumptions on which it implicitly rests. As we shall see, once those assumptions are made explicit and critically examined, many common arguments on what happened and who is to blame for it fall apart. I hope that, at the very least, I will convince even the skeptical reader that things are more complicated than they seem. Below you can find the first essay of the series in which I explain why the hopes of 1989 have not been fulfilled and instead Europe is now engulfed in the largest war on the continent since WWII.

Summary

Did the US and its allies promise the Soviet Union that there would be no NATO expansion at the end of the Cold War? This question has caused considerable controversy, as successive Russian leaders have made this claim over the past 30 years and accused the West of breaking their pledge by expanding NATO to Central and Eastern Europe.

As revolutions swept through Central and Eastern Europe and the Cold War drew to a close in 1989, German reunification was the most pressing issue to settle the conflict. But it required Moscow’s approval due to legal rights inherited from the end of WWII and the presence of a massive contingent of Soviet troops in the German Democratic Republic (GDR).

The central question was whether united Germany would be allowed to stay in NATO after reunification or whether it would have to leave the Alliance and adopt some kind of neutral status. Indeed, with the end of the Cold War, it wasn’t even clear whether NATO should continue to exist.

Most scholars have sided against Russia in arguing that no such pledge had been made during the negotiations on German reunification and more generally that the West didn’t have any obligation not to expand NATO as a result of the commitments made at the end of the Cold War.

The debate has focused on statements made by US and West German officials during preliminary talks held on the issue in February 1990. While everybody agrees that on this occasion they pledged not to expand NATO to the east if Germany was allowed to stay in the Alliance, people disagree about what they meant and what implications those exchanges had.

Critics of the Russian position argue that they were only talking about the territory of the GDR, that Gorbachev didn’t take even this limited no-expansion deal and that it was subsequently retracted anyway. Defenders of the Russian position argue that US and West German officials were talking about Central and Eastern Europe as a whole and that some kind of implicit deal ruling out NATO expansion to that area was in fact struck.

I argue that although they often overstate it, the Russians nevertheless have a strong case for a weak version of their claim, but that it’s not for the case defenders of their position typically make. Conversely, critics of the Russian position are right that US and West German officials were only talking about the GDR (with one important exception about which they misrepresent the evidence), but it’s not for the reasons they claim.

Moreover, they mistakenly conclude that Western officials didn’t make assurances that ruled out NATO expansion because, like defenders of the Russian position, they misconstrue the dynamic of the negotiations on German reunification and focus on the preliminary talks held in February 1990 at the expense of the rest of the negotiations.

I argue that Western officials never proposed a quid pro quo to their Soviet counterparts, at least not the quid pro quo that both critics and defenders of the Russian position have suggested. Gorbachev was not the naive negotiator usually portrayed, but was severely constrained by the fact that achieving his main policy goals required maintaining a cooperative stance with the West.

This led him to consent to German reunification in NATO, but he also accepted because he was assured repeatedly by Western officials that it would be followed by the creation of an inclusive post-Cold War European security order. I argue that NATO expansion, which instead created a NATO-centric security architecture that excluded Moscow, was a violation of those assurances.

The most significant aspect of this controversy, however, is not so much whether the US and its allies violated a pledge not to expand NATO made at the time, but the decision by the Bush administration to preserve NATO’s primacy in the post-Cold War era instead of pursuing a pan-European security agenda.

I conclude by reflecting on this road not taken at the end of the Cold War and argue that the Bush administration’s decision not to follow it, which I explain was made for both good and bad reasons, made the subsequent deterioration of relations between Russia and the West and a conflict between Ukraine and Russia, while by no means inevitable, much more likely.

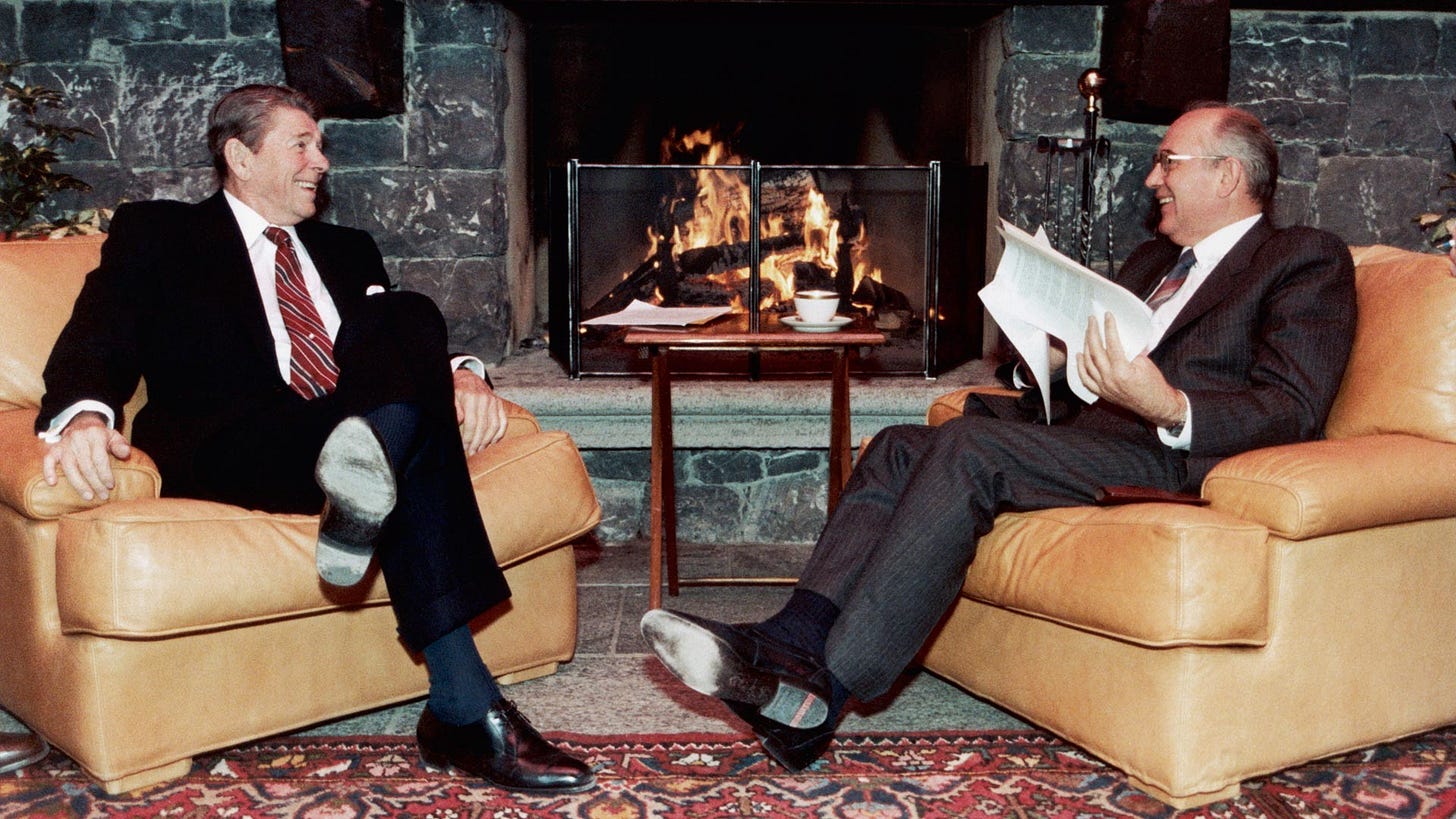

In 1985, after the death of Konstantin Chernenko, Mikhail Gorbachev was elected General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). In the years that followed, he launched a series of wide-ranging reforms that undermined the CPSU's monopoly on power, ended the Cold War and eventually led to the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Despite widespread misconceptions, Gorbachev decided to end the Cold War not because he had no choice (while the Soviet Union was already in crisis at the time it still had the means to continue to wage the Cold War), but rather because he came to reject the ideological underpinning of the East-West confrontation. Paradoxically, he was able to succeed in ending the Cold War because he found a willing and enthusiastic partner in Ronald Reagan, who then as now was considered the arch-Cold Warrior. Reagan came to power with the conviction that something had to be done to reduce the threat posed by nuclear weapons, but he was critical of the détente because he thought that it had disproportionately benefited the Soviet Union, so he adopted a policy that combined firmness to force the Soviets to the negotiating table with a genuine willingness to make substantial reductions in nuclear weapons once they did. Although initially skeptical, Reagan came to trust Gorbachev after meeting him and became convinced that he was serious about reforming the Soviet Union and democratizing it, leading to a fruitful cooperation and a transformation of US-Soviet relations that ended the Cold War.3

In 1987, the two leaders signed the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Force Treaty (INF Treaty), which closed the Euromissile Crisis started by the Soviet Union's decision to deploy SS-20 missiles targeting Western Europe at the end of the 1970s and was the first arms reduction agreement to eliminate a whole category of weapons. They also resumed the negotiations on the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START Treaty), which had begun in 1982 but had stalled after Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative in 1983, although it would not be signed until 1991 under George H. Bush. Moreover, Gorbachev started to reduce the number of troops that were stationed in Warsaw Pact countries, although hundreds of thousands remained. In December 1988, he made a speech at the UN in which he rejected the use of force in foreign policy and declared that Central and Eastern Europeans should be free to decide what kind of political and economic system they wished to live under, which amounted to a rejection of the Brezhnev Doctrine and made people in the West realize that he was serious about reforms.4 A few months later, his intentions were put to the test when Central and Eastern European countries moved toward liberalization and started the process that would result in the collapse of socialism in the Eastern bloc. But Gorbachev stood firm and, in a speech he gave at the Council of Europe in July, repeated his pledge that the Soviet Union would not use force to stop that process.5

In August 1989, a peace demonstration was held on the Austro-Hungarian border and the border was briefly opened, which set in motion a chain of reaction that resulted in the disintegration of the Soviet bloc. By the end of the year, after a series of revolutions, communist regimes had been swept away everywhere in Central and Eastern Europe and replaced by democratic political systems with competitive elections. In September, the Hungarian authorities decided to open the border with Austria, which led to the exodus of thousands of East Germans and further increased the pressure on the German Democratic Republic to open up. Mass protests erupted in East Germany and, by October, Erich Honecker, the leader of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was forced to resign. On November 9, the spokesman of the regime gave a press conference to announce new travel regulations, but in talking to journalists he gave the impression that East Germans were now free to cross the border in Berlin. The news spread quickly and, a few hours later, a very large crowd had gathered at the Wall and demanded to cross to the West. Since no one was willing to take the responsibility to use force to disperse the crowd, the commander at one of the border crossings yielded and ordered the guards to let people through.6 Almost 40 years after it was erected, the Berlin Wall had fallen and the German reunification, which up until then had seemed but a distant hope, suddenly appeared inevitable.

However, it would require negotiations with the Soviet Union, which still had more than 300,000 troops on the territory of the GDR and legal rights over Germany due to the post-World War 2 arrangements under which Germany was to be administered by the victorious powers. These negotiations took place throughout 1990 and, in the years and decades that followed, have become the topic of a controversy between the West and Russia. Moscow claims that, during the negotiations, Western officials had pledged not to expand NATO to Central and Eastern Europe to convince Gorbachev to allow Germany to remain in NATO after reunification. As we shall see, although today this argument is commonly associated with Vladimir Putin (who frequently brings up this old grievance to justify his actions), it has a long history that started well before he rose to power and did not originate with him.7 It's important to examine this controversy because, although ultimately I will argue that it’s not as important as many people who are sympathetic to the Russian argument believe, I think it illustrates how Russia's complaints are summarily, and sometimes even dishonestly, dismissed in the West even when they have merits. This kind of attitude goes a long way toward explaining why Moscow came to distrust the West in the decades since the end of the Cold War, even if taken in isolation this particular episode didn't matter as much as the importance it has taken in the public debate suggests. This controversy also highlights how key decisions that were made by the US and its allies at the end of the Cold War and, beyond the particular issue of NATO expansion, shaped the relations between Russia and the West in the post-Cold War era.

1 The controversy about the pledge not to expand NATO

As I just noted, the controversy about the pledge that Western officials allegedly made not to expand NATO to Central and Eastern Europe at the end of the Cold War did not originate with Putin. Russian officials have offered several different versions of that argument over the years and it’s not always easy to pin down exactly what claims they are making. A version of that argument was made in 1993 by Boris Yeltsin in a letter that he sent to Bill Clinton:

I also want to call attention to the fact that the spirit of the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany, signed in September 1990, especially its provisions that prohibit the deployment of foreign troops within the eastern lands of the Federal Republic of Germany precludes the option of expanding the NATO zone into the east.8

This claim was not only vague but also pretty weak, since in particular he was just talking about the “spirit” of the treaty on Germany’s reunification, but later in the 1990s Russian officials made stronger arguments that referred more specifically to claims made by Western officials at the end of the Cold War.9 More recently, in the speech he made just before the invasion of Ukraine, Putin also referred to the promise that Moscow had allegedly received in 1990 and was more specific:

In 1990, when German unification was discussed, the United States promised the Soviet leadership that NATO jurisdiction or military presence will not expand one inch to the east and that the unification of Germany will not lead to the spread of NATO's military organization to the east. This is a quote.10

As we shall see, the quote he seemed to have had in mind was a statement made by James Baker, who in 1990 was Secretary of State. In 2009, Dmitry Medvedev, then President of Russia, had also accused the West of having broken promises that were made at the time:

After the disappearance of the Warsaw Pact, we were hoping for a higher degree of integration. But what have we received? None of the things that we were assured, namely that NATO would not expand endlessly eastwards and our interests would be continuously taken into consideration. NATO remains a military bloc whose missiles are pointed towards Russian territory. By contrast, we would like to see a new European security order.11

It’s interesting to note that, in Medvedev’s version of the argument, NATO expansion was part of a more general complaint about the West’s attitude toward Russia after the end of the Cold War. In order to understand what they were talking about, it’s necessary to go back to what happened after November 8, 1989.

Three weeks after the fall of the Wall, Helmut Kohl, then Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), made a speech in the Bundestag where he presented a ten-point plan to reunify Germany. In this speech, he proposed in particular that, as a first step toward unification, a German confederation be created that would bring together the FRG and the GDR. But he made that proposal without consulting either Gorbachev or his Western allies, which raised concerns both in the Soviet Union and the West that he might try to act unilaterally and present them with a fait accompli. Gorbachev was particularly upset because, after the Wall fell, he’d sent a personal envoy to Kohl enjoining him to proceed with caution and promising that if he did then “anything might become possible”, so he thought that by making that speech without talking to him first Kohl had violated their agreement.12 As a result, he refused to discuss reunification for 2 months after that, which gave Kohl time to reassure his Western allies. They were also concerned that he’d made that announcement without consulting them and, ironically, suspected that he might have made a deal behind their back with Gorbachev. François Mitterrand, the French president, accepted reunification without enthusiasm but wanted to make sure that it would not imperil European integration and that post-WWII borders would not be questioned. Margaret Thatcher, the British Prime Minister, was opposed to reunification because she feared Germany would go bad again. While eventually she accepted that she couldn’t prevent it and aligned herself with the US position, she secretly hoped that Gorbachev would stop it. As for George Bush, the US president, he supported German reunification as long as it did not threaten NATO, which then as now was the main vehicle of US influence in Europe. In January, the Soviets reached the conclusion that reunification was inevitable, so they agreed to host US and West German officials in Moscow on February 9-10 for preliminary talks on the issue.

The controversy has focused on what US and West German officials told their Soviet counterparts during those preliminary talks in Moscow. As we shall see, they made some assurances that NATO would not expand to the east, but people disagree about what they meant by that. The Russians and people who defend their position claim that, when US and West German officials told the Soviets that if Germany could stay in NATO after reunification the Alliance would not move eastward, they were not just talking about the territory of the GDR but about Central and Eastern Europe in general. Most Western officials, on the other hand, insist that the assurances made in Moscow only pertained to the GDR. For instance, then Secretary of State Baker, who as we shall see played a crucial role in the negotiations over German reunification, repeatedly made that claim and denied that the Russian argument had any merit:

There was a discussion about whether the unified Germany would be a member of NATO, and that was the only discussion we ever had. And the Soviets signed a treaty acknowledging that the unified Germany would be a member of NATO. So I don't understand how they can have these ideas that somehow, now, we promised them there would be no extension of NATO. There was never any discussion of anything but the GDR.13

This is also the view expressed by Philip Zelikow, who in 1990 was on the staff of the National Security Council (NSC) dealing with those issues. In a 1995 op-ed, he claimed that “there is no evidence that in late January or early February of 1990 anyone — Mr. Genscher, James Baker or Mikhail Gorbachev — was even thinking, much less talking, about the possibility of NATO expansion even further into East-Central Europe”.14 Rodric Braithwaite and Hans-Dietrich Genscher, respectively UK ambassador to the Soviet Union and foreign minister of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) in 1990, more recently expressed a similar opinion.15

Until a few years ago, this position had also become a near-consensus among scholars. Its most influential defense is probably a paper by Mark Kramer published in 2009, where he argued that the idea that Western officials had pledged not to expand NATO if the Soviet Union agreed to allow reunified Germany to stay in NATO was a "myth".16 Angela Stent, citing that paper among other things, recently summarized that position:

What did the West promise Gorbachev at the time of German unification? This question has riled relations for more than twenty years, reinvigorated as more archival material has become available. Some Western participants in the German unification process insist that the United States promised Gorbachev that NATO would not enlarge after Germany was unified and accuse the West of reneging on commitments it made to the USSR. Many Russian officials and experts, including Mikhail Gorbachev himself, subscribe to this view. “According to the Two-Plus-Four Agreements under which Germany was unified,” he has said, “the United States, Germany, Britain and France promised us that they would not expand NATO east of Germany.” Yet a careful reading of the agreements that were signed in 1990 when a united Germany joined NATO reveals that NATO enlargement was not explicitly addressed. Gorbachev and his advisors may have with hindsight believed that promises had been made by the Americans. But the historical record shows that no explicit commitments about NATO not enlarging were made—simply because this issue was not on the table. Secretary of State James Baker had told Gorbachev in February 1990 (before Germany was unified) that NATO’s jurisdiction would not shift eastward from its present position, but he was referring to NATO’s jurisdiction over the territory of the GDR, not to NATO’s possible enlargement. In other words, Baker was talking about not stationing NATO troops on the territory of the former East Germany after 1990, not about anything else.17

For a long time, this view was virtually unchallenged in academic circles, but this changed a few years ago when new archival documents emerged and some scholars started to argue that, in light of that evidence, Kramer's position had to be revised.

This actually started in 2009, the same year Kramer published his paper, when Der Spiegel published a piece saying that "after speaking with many of those involved and examining previously classified British and German documents in detail, SPIEGEL has concluded that there was no doubt that the West did everything it could to give the Soviets the impression that NATO membership was out of the question for countries like Poland, Hungary or Czechoslovakia".18 But it took a few years before academics, using the documents cited by Der Spiegel and other recently declassified materials, started to push back against Kramer's view. In 2016, Joshua Shifrinson published a much noted paper in which he reopened the debate and, using recently declassified documents, argued that despite the consensus "this evidence suggests that Russian leaders are essentially correct in claiming that U.S. efforts to expand NATO since the 1990s violate the ‘spirit’ of the 1990 negotiations".19 Svetlana Savranskaya and Thomas Blanton made a similar argument in 2017, concluding that "multiple national leaders were considering and rejecting Central and Eastern European membership in NATO as of early 1990 and through 1991, that discussions of NATO in the context of German unification negotiations in 1990 were not at all narrowly limited to the status of East German territory, and that subsequent Soviet and Russian complaints about being misled about NATO expansion were founded in written contemporaneous memcons and telcons at the highest levels".20 More recently, Marc Trachtenberg published a paper in which he defends a similar view, concluding that "the Russian allegations are by no means baseless".21 Previously, Mary Sarotte had somewhat nuanced Kramer’s position, arguing that contrary to what he claims the expansion of NATO not only to East Germany but also to Central and Eastern Europe was briefly discussed in 1990, though in the end Gorbachev never secured a promise that it would not happen and even made concessions on East Germany in the final agreement that undermined the principle that NATO could not expand eastward.22 Kristina Spohr is generally close to Kramer's position, but she nevertheless acknowledges that several Western officials "did make comments to Soviet officials that might have been interpreted as more far-reaching and thus perhaps more consequential in terms of Soviet perceptions than has so far been acknowledged".23

Before Russia invaded Ukraine, those arguments had weakened the consensus in favor of Kramer's position, but since then it has become unpopular to acknowledge that some of Putin's complaints may have merits, so now people tend to talk as if the debate of the last few years had never happened and the view that Russia's position has no merits whatsoever once again goes largely unchallenged. In what follows, I argue against that view and conclude that the conclusion reached by Der Spiegel is essentially correct, while acknowledging that the case for the Russian position has nevertheless been exaggerated. In particular, I show that critics of that position are right about a crucial aspect of that debate (though for the wrong reasons), namely the scope of the assurances made in Moscow during the preliminary talks on Germany’s reunification in February 1990. With one exception, US and West German officials who participated in those preliminary talks were only talking about the territory of the GDR, but I argue that it doesn’t follow that NATO expansion to Central and Eastern Europe didn’t violate assurances made at the end of the Cold War because the negotiations on Germany’s reunification continued for several months after that and Western officials subsequently made broader assurances that it was very reasonable for the Russians to retrospectively consider incompatible with NATO expansion. But perhaps more importantly, this discussion will highlight a key but largely ignored fact about this controversy, which is that even if the debate has so far narrowly focused on the issue of NATO expansion, what violated the assurances made by Western officials at the end of the Cold War wasn’t so much NATO expansion per se but the gradual exclusion of Russia from the European security architecture it came to imply. In order to understand why, however, it’s necessary to go back to the controversy as it has played out in the literature and the arguments made by critics of the Russian position. In his paper on the controversy, Trachtenberg distinguishes three main arguments that critics of the Russian position have made:

First, they claim that the assurances applied only to eastern Germany, and not to Eastern Europe as a whole, and that even those assurances were superseded by arrangements worked out with the USSR later in the year. Second, they claim that the assurances in any event were not legally binding, and were thus not binding at all, because they were not embodied in any formal, signed agreement. And, third, they insist that whatever impression the Russians took away from what they had been told, western leaders had not deliberately sought to mislead them.24

He goes on to argue, often that each of those arguments is flawed. In what follows, I will also examine those arguments and explain why, though on most points his position is correct and I’m in broad agreement with him, I nevertheless think Trachtenberg sometimes overstates his case or doesn’t frame his position in the right way.

1.1 The assurances made at the beginning of the Two Plus Four process

Everybody agrees that, when he saw Gorbachev on February 9, 1990, Baker told Gorbachev that "if we maintain a presence in a Germany that is a part of NATO, there would be no extension of NATO’s jurisdiction for forces of NATO one inch to the east".25 But as we have seen, most former Western officials and scholars claim that this and other similar assurances given by Western officials in the course of the negotiations about Germany's reunification only applied to the territory of the GDR. Moreover, they argue that even those assurances about East Germany were superseded by concessions made by Gorbachev later in the negotiations, as reflected by the content of the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Germany or Two Plus Four Agreement by which France, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the United States renounced the rights they held on Germany and allowed reunification between the FRG and the GDR. As Trachtenberg notes, when people claim that assurances made during the negotiations of this treaty only concerned the territory of the GDR and not the rest of Central and Eastern Europe, they actually make two distinct arguments.26 First, they argue that the expansion of the NATO beyond the Oder-Neisse line (which constituted the border between the GDR and Poland) was simply not an issue at the time, because at least when Baker said that nobody envisioned the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact. If that were true, then it would settle the question, because if nobody was even thinking about the possibility that NATO might expand to Central and Eastern Europe at the time then Baker couldn't have been talking about this when he told Gorbachev that NATO would not move "one inch to the east". As Trachtenberg points out, the second argument is narrower in scope and says that whatever the participants had in mind at the time, the issue of NATO expansion to Central and Eastern Europe never came up during the negotiations and the assurances to which people who find merits in the Russian argument refer applied only to the GDR.

1.1.1 The context of the preliminary talks in Moscow between US/FRG officials and their Soviet counterparts

Starting with the first argument, as Trachtenberg and others have pointed out, it's patently false that nobody envisioned that the Warsaw Pact would disappear and that NATO might expand to former members of that organization in February 1990. On the Soviet side, Kramer claims that in February 1990, "Gorbachev was still fully confident that the USSR would continue to ‘work with its allies’ in the Warsaw Pact", but Soviet archives of a Politburo meeting on January 2, the British record of a meeting between Eduard Shevardnadze and Douglas Hurd, respectively Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union and Foreign Minister of the UK, on February 12 and a diary entry by one of Gorbachev's aides for January 21 show that, on the contrary, many people in the Soviet leadership were already predicting the end of the Warsaw Pact by then.27 For instance, in his meeting with Hurd, Shevardnadze is reported as saying:

If [the GDR] ceases to exist, Soviet troops will be pulled out of Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Poland also will not want them. What purpose then would the Warsaw Pact have?

He said that at a time when, by everyone's account, the Soviet government had reached the conclusion that Germany's reunification was inevitable and that it would happen soon, so it's obviously not the case that nobody on the Soviet side was thinking about the end of the Warsaw Pact in February 1990. While Gorbachev himself was still talking as if he believed that at least part of it could be saved in a meeting with some of his advisors on January 26, as Trachtenberg notes, he was hardly "fully confident" that it would remain intact.28

In the West, not only had intelligence services been predicting the disintegration of the Warsaw Pact since the end of 1989, but the press was openly speculating that its days were numbered by the beginning of 1990.29 On February 4, just a few days before Baker met with Gorbachev and gave his infamous assurance that NATO would not move "one inch eastward", The Washington Post published a piece whose title was "Warsaw Pact—Endgame: In Eastern Europe, the Military Alliance Is Dead" and in which the author reported that "many top U.S. and European officials confidently predict" that "Soviet troops will be forced to withdraw entirely from Eastern Europe within a few years" and that "Hungary and perhaps Czechoslovakia may formally withdraw from the Warsaw Pact". A bit later in the article, he even added that "the idea of an entire nation defecting from the Warsaw Pact is hardly surprising, given that the alliance has already ceased to function substantively".30 On January 19, The Washington Post had already reported that "Hungarian and Polish leaders said today they want all Soviet troops out of their countries in a year or two, underscoring the increasingly rapid dissolution of the Warsaw Pact as a military alliance".31 During a public seminar organized by a German defense magazine on February 3-4, Gerhard Stoltenberg, the Minister of Defense of the FRG, declared that "we would commit a fatal strategic mistake if, faced with the increasing disintegration of the Warsaw Pact, we negotiated in exchange that of the Atlantic Alliance".32 Recently declassified British and US documents, as well as interviews with former Bush administration officials, also show that by the end of 1989 and the beginning of 1990, the White House was already thinking about how to increase US influence in Central and Eastern Europe after the Soviet Union retreated from the region, so obviously they expected this to happen.33 Thus, while nobody at the time expected that it would happen so fast, few people doubted that in the long run the Warsaw Pact would disappear or, at the very least, that it would not survive without undergoing a significant transformation that would open the door to more US and Western influence in Central and Eastern Europe.

But the fact that people expected the Warsaw Pact to disappear and more generally Soviet influence to wane in the region doesn't mean they were already planning to expand NATO. Indeed, while Bush and his advisors were already concerned with making sure to keep their options open when the negotiations over German reunification started, they did not begin to seriously consider offering Central and Eastern European countries the prospect of NATO membership until 1991 and it wasn’t until Bush’s final year in office that a consensus developed that it would have to happen eventually because it was the best way to strengthen the US position in the region and prevent a dangerous standoff between Russia and Germany did not emerge until Bush's final year in office.34 However, in a speech he gave in Tutzing on January 31, Genscher not only endorsed Gorbachev's idea of a pan-European security architecture, but he publicly called for NATO to "state unequivocally that whatever happens in the Warsaw Pact, there will be no expansion of NATO territory eastward, that is to say, closer to the borders of the Soviet Union".35 Immediately before that, he had noted that in “Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary there is a growing demand for the withdrawal of Soviet forces” and that “we cannot say for sure at present what impact this will have on the structure, and on the future, of the Warsaw Pact”, clearly implying that it might unravel. If he had just said that NATO would not expand "closer to the borders of the Soviet Union", this sentence would be ambiguous on whether he was merely referring to the territory of the GDR or more generally to Central and Eastern Europe, but the fact that he prefaced this claim by "whatever happens to the Warsaw Pact" immediately after, strongly implying that it might soon cease to exist, in addition to being more evidence that Western officials already suspected that the Soviet-led alliance would not survive at the beginning of 1990, makes it clear that he meant the latter.

Yet when he mentions that speech, Kramer paraphrases Genscher as saying that “a united Germany would be a member of NATO, but that NATO’s jurisdiction would not extend to the eastern part”, which falsely makes it sound as if he was only talking about the territory of the GDR.36 Nor was Genscher’s wording a mistake or something he’d let slip in the heat of the moment, for he repeated the same thing almost word for word in a speech he made in Potsdam on February 9, just one day before he met with Shevardnadze in Moscow.37 It’s true that just after the passage where he made that non-expansion assurance, Genscher also said explicitly that “any proposals for incorporating the part of Germany at present forming the GDR in NATO’s military structures would block intra-German rapprochement”, but it’s clear that at this point of the speech he’s moved on to a different, though related point.38 To be sure, it’s also possible to interpret Genscher as saying that NATO should commit not to expand to the territory of the GDR even if the Warsaw Pact collapsed (in which case one might think that Moscow would care less about what happened in the territory of the GDR), but this interpretation seems far less natural and, as we shall see shortly, there is more evidence that it’s not what Genscher meant and that he was talking about Warsaw Pact countries. Moreover, even if that interpretation were correct, it wouldn’t really help critics of the Russian position. Indeed, if the Soviet Union was so concerned about NATO that Genscher thought it was important to promise that it would not expand to the territory of the GDR even if the Warsaw Pact collapsed, then a fortiori this assurance would have applied to former Warsaw Pact countries in Central and Eastern Europe. Not only did the assurances made by Genscher extend far beyond the GDR, but officials in Washington seem to have noticed and were alarmed by it. Robert Hutchings, who in 1990 served as a special advisor to the Secretary of State, later wrote about Genscher’s speech in Tutzing that he was speaking “not about the GDR but about Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary”.39 It would be very surprising if Soviet officials had not also noticed. Indeed, Gorbachev discussed in some detail the range of views that had been expressed at the symposium of the Protestant Academy in Tutzing on January 31 when he met Baker in Moscow on February 9, so it’s hard to believe that he didn’t read Genscher’s speech, which was delivered at the same event.40 Shevardnadze also claimed to have read the speech he made in Potsdam and even to have forwarded it to Gorbachev.41

Moreover, just one week before his fateful meeting with Gorbachev in Moscow, Baker went along with this idea or at least did nothing to suggest that he didn't even when the opportunity to do so came along. Indeed, after he gave that speech, Genscher decided to meet with Baker in Washington on February 2 to make sure they were on the same page and, according to a cable about the meeting sent by the State Department I discuss below, he told him there was a "need to assure the Soviets that NATO would not extend its territorial coverage to the area of the GDR nor anywhere else in Eastern Europe for that matter" and Baker apparently did not express a disagreement with that idea.42 Genscher then went on to repeat that point in the press conference he and Baker gave after their meeting, during which he made the following remarks as Baker was standing next to him:

We agreed that the intention does not exist to extend the NATO defense area toward the East. That applies, moreover, not just to the territory of the GDR, which we do not want to incorporate, but rather applies in general.43

He could hardly have been clearer that, contrary to what critics of the Russian position claim, he was not just talking about the territory of the GDR but about Central and Eastern Europe in general. As Trachtenberg notes, the fact that he used "we" is also significant, because it means that he was speaking for both he and Baker. If Baker had wanted to express his disagreement with that proposal, he could have done so during the press conference, but he did not.

One could argue that Baker may have missed the significance of that point since at the time everyone was still focused on the issue of whether Germany would be allowed to remain in NATO after reunification in the first place, which pushed the question of the conditions under which the Soviet Union might agree to that in the background.44 However, a summary of their discussion sent by the State Department to the US Ambassador to the FRG at Baker's request shows that he, or at least the author of that cable, Assistant Secretary of State for Europe and Canada Raymond Seitz, did not miss this part of Genscher's proposal at all:

Genscher confirmed that neutrality for a united Germany is out of the question. The new Germany would remain in NATO because NATO is an essential building block to a new Europe. In stating this, Genscher reiterated the need to assure the Soviets that NATO would not extend its territorial coverage to the area of the GDR nor anywhere else in Eastern Europe for that matter. (He made this point with the press after the meeting.)45

Moreover, in describing Baker's response to Genscher's proposals, the cable does not say that Baker expressed disagreement with that idea at any point during that conversation. As Sarotte explains, the reason why this cable was sent to Bonn is that Baker wanted the US Ambassador to the FRG to inform Kohl, the German Chancellor, of what had been discussed in Washington because he wasn't sure that Genscher, who didn't have a very good relationship with Kohl, would do so and he wanted to make sure that everyone both in Washington and Bonn was on the same page before the negotiations with the Soviet Union started. Vernon Walters, the US Ambassador to the FRG, did as instructed and briefed Horst Teltschik, Kohl's security advisor, the next day.46 Thus, not only was the State Department in Washington aware that Genscher wanted to give Moscow assurances that applied not just to the territory of the GDR but to Central and Eastern Europe in general, but so was the Chancellor's office in Bonn and as far as we can tell neither raised any objections.

Finally, to remove any lingering doubt that US officials may have missed that Genscher's proposal applied not only to the territory of the GDR but to Central and Eastern Europe in general, the State Department official transcript of his press conference with Baker makes Genscher's remarks even more explicit than they already were:

Perhaps I might add, we were in full agreement that there is no intention to extend the NATO area of defense and the security toward the East. This holds true not only for GDR, which we have no intention of simply incorporating, but that holds true for all the other Eastern countries. We are at present witnessing dramatic developments in the whole of the Eastern area, in COCOM, and the Warsaw Pact. I think that it is part (of) that partnership in stability which we can offer to the East that we can make it quite clear that whatever happens within the Warsaw Pact, on our side there is no intention to extend our area—NATO’s area—of defense towards the East.47

So people in the State Department, but probably also in the NSC, had duly noted the scope of Genscher's proposal and, if US officials did not express disagreement with it either publicly or privately, it's not because they had missed it.48

At the time, US officials were not only worried that the Soviet Union might adamantly reject that a reunified Germany remain in NATO, but they also feared that Gorbachev might offer Helmut Kohl a deal he "couldn't refuse" by proposing to allow reunification in exchange for neutrality.49 This would effectively spell the end of NATO and, as a result, of the US military presence in Europe, something US officials were determined to prevent. Thus, it's possible that Baker didn't actually intend to give the Soviet Union assurances that went beyond the territory of the GDR, but thought it best not to raise that issue with Genscher at this time to avoid a split between the US and Germany.50 In fact, this is more or less what James Dobbins, then Assistant Secretary of State for Europe, told the British Ambassador in Washington after Baker’s meeting with Genscher:

Immediately after the meeting Genscher announced to a hastily assembled press conference that he and Baker were in ‘full agreement’ that reunification would not involve the extension of NATO to the east. Dobbins said that Baker had not in fact blessed Genscher’s particular formula, even though it was the best available at present. The Administration has made its position clear in December with its four principles, and was now cautious about being too specific, lest it be interpreted by the German opposition as an imperial dictat [sic] or upset the Russians before Baker’s talk with Shevardnadze.51

Thus, it seems that at the time Baker wasn’t ruling out Genscher’s formula, but he may also have not been committed to it and simply remained silent for tactical reasons when Genscher publicly said he had endorsed it. However, it’s also possible that Baker was initially more aligned with Genscher’s position, that he revised his view later after other people in the Bush administration pushed for a less accommodating stance and that Dobbins was engaging in damage control after the fact with allies.52 This might also explain why, as we shall see, Baker remained somewhat ambiguous when he met Shevardnadze and Gorbachev in Moscow. The most important thing for US officials at the time was that Genscher had said that Germany had to stay in NATO after reunification and they wanted to make sure he would not move from this position.

In any case, it's remarkable that even though several critics of the Russian position actually quoted this passage of the press conference during which Genscher talks about the necessity to make clear that NATO would not expand to the east, they omitted the part where he makes clear that he isn't merely talking about the territory of the GDR but about Central and Eastern Europe in general. For instance, Zelikow and Rice claim that "Baker understood Genscher to say that Germany would remain in NATO, but the Soviets had to be assured that NATO's territorial coverage would not extend to the former GDR" and quote Genscher's comment that he and Baker "were in full agreement that there is no intention to extend the NATO area of defense and security towards the East", which comes from the State Department’s transcript of the press conference, but omit the next sentence in the transcript, where Genscher clarifies that it "holds true not only for GDR, which we have no intention of simply incorporating, but that holds true for all the other Eastern countries".53 Spohr wrote that Genscher’s discussion with Baker “left the territories east of the GDR untouched”, but as we have seen that is simply not true.54

Kramer even went further and, after quoting the exact same part of the transcript as Zelikow and Rice (without the next sentence that clarified the scope of his assurance that NATO would not expand "towards the East"), he added a gloss on that comment that completely changed the meaning of what Genscher had actually said:

At a joint press conference after their meeting, Genscher said that he and Baker "were in full agreement that there is no intention to extend the NATO area of defense and security toward the East," meaning eastern Germany. [emphasis is mine] When asked by journalists what exactly this meant, Genscher insisted that he was not talking about "a halfway membership [for a united Germany] this way or that. What I said is there is no intention of extending the NATO area to the East."55

Kramer cites a Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung article as the source of those quotes, but it doesn't actually contain them and they are identical to the State Department transcript, so either he checked the transcript directly or he found those quotes in another source that was quoting Genscher from the transcript.56 Whether he knew that Genscher had made clear that he was talking not just about the territory of the GDR but about Central and Eastern Europe in general and knowingly altered the meaning of his remarks by adding that gloss or was misled by another source that quoted Genscher partially and added that gloss in good faith, the fact is that he completely changed the meaning of Genscher's remarks in a way that makes them consistent with his view that Western officials never made any assurances that went beyond the territory of the GDR, when in fact they show that view to be false. As we shall see, adding interpolations to ambiguous statements made by Western officials pledging not to expand NATO eastward to make them sound like they support his view that assurances given about NATO expansion only ever applied to the territory of the GDR is part of Kramer's usual modus operandi, but in this case he actually did the same thing with a statement that was not ambiguous at all.57 As we have seen, he had already distorted Genscher’s Tutzing speech in a similar way.

On February 6, Genscher met with Douglas Hurd, the British Foreign Minister, in Bonn and told him the same thing. Here is how the latter summarized what Genscher had told him in a cable he sent to Christopher Mallaby, the British Ambassador to the FRG, after their meeting:

Genscher added that when he talked about not wanting to extend NATO that applied to other states beside the GDR. The Russians must have some assurance that if, for example, the Polish Government left the Warsaw Pact one day they would not join NATO the next.58

A German document summarizing the same meeting says that Genscher told Hurd something very similar, but using the example of Hungary instead of Poland:

The West could do a lot to facilitate the current developments for the SU. Of particular importance was the declaration that NATO had no intention of expanding its territory to the east. Such a declaration should not only relate to the GDR, but should be of a general nature. For example, the SU also needs security that Hungary will not become part of the western alliance in the event of a change of government.59

According to Hurd's cable, Genscher also told him that "the CSCE summit, devoted to the future of Europe, would be an important vehicle for helping the Soviet Union to come to terms with the erosion of the Warsaw Pact", which again show that both the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the possibility that Moscow might worry about the expansion of NATO in that area were very much on the mind of Western officials just before the negotiations about German reunification were set to begin.60

The possibility that NATO might expand to Central and Eastern European countries or at least that Western countries might expand their influence in that region as the Soviet Union retreated from it was certainly on the mind of leaders in those countries. Indeed, on February 4, The Washington Post reported that it was a "hot topic of discussion" among military leaders in the Warsaw Pact:

But the shopworn, bipolar concept of Europe no longer interests military leaders of the Eastern bloc, many of whom have been swept into power within the past two months. In their circle, the prospect of a militarily neutral Eastern Europe, or even one with a web of economic and military ties to the West, is suddenly a hot topic of discussion.61

Gyula Horn, Hungary's Foreign Minister, actually talked about the possibility that his country might join "NATO's political councils" publicly on February 24.62 He had even raised the idea directly to Lawrence Eagleburger, the Deputy Secretary of State, in a private meeting around the same time.63 In the months that followed, as they realized that Gorbachev would not use force to prevent the dislocation of the Warsaw Pact, leaders of Central and Eastern European countries started to be increasingly explicit about their interest in eventually joining NATO. Kramer is right that, in his statement, Horn was not talking about joining NATO's military structures but merely about some kind of political cooperation and that he said that more than 2 weeks after Baker met Gorbachev, but The Washington Postarticle makes clear that Eastern European leaders had already talking about it privately before that. Now, if leaders of Warsaw Pact countries were talking about this even before Baker went to Moscow, it's very unlikely that Soviet officials didn't know about it. Indeed, in a January 26 meeting with his advisors I already mentioned above, Gorbachev explained that unless the Soviet Union worked with "other socialist countries" they'd be "picked up by others", by which he presumably meant NATO.64

Thus, the argument that Western officials couldn't possibly have intended to give assurances about NATO expansion that applied to Central and Eastern Europe in general and not just the territory of the GDR in February 1990, because nobody at the time imagined that the Warsaw Pact would collapse and that NATO might expand in the region, is undoubtedly incorrect. To be sure, in both private and public conversations in the days and weeks leading up to the beginning of the negotiations over German reunification, the focus was on the status of the territory of the GDR, but officials in both the Eastern and Western blocs definitely had in mind the unraveling of the Warsaw Pact and the possibility that Western countries might take advantage of it, including by expanding NATO even though nobody was actively planning to do so at the time. As we have seen, Genscher even gave public assurances to that effect that it wouldn't happen on several occasions, including during a press conference where he claimed to be speaking for both he and Baker, yet as Trachtenberg aptly noted neither Baker during that press conference nor the State Department later "issue a clarification pointing out that Genscher had been speaking only for himself when he had made that remark and that the U.S. government did not necessarily share his views in that regard".65 Which brings us to the second, narrower argument that, whatever people were thinking when the negotiations about Germany's reunification started, nothing was said during the negotiations to the effect that NATO would not expand to Central and Eastern European countries and Western officials only gave assurances about the territory of the GDR.

1.1.2 What US and West German officials told their Soviet counterparts in Moscow

Baker went to Moscow on February 9 and first met with Shevardnadze before talking to Gorbachev. He tried to convince both that it would be in the Soviet Union's interest to allow Germany to stay in NATO after reunification, on the grounds that a neutral Germany would probably seek to develop an independent nuclear capability to ensure its security and might even return to the militarism of the past, which would be much less likely if it remained anchored in NATO. He told Shevardnadze that, in that case, "there would, of course, have to be iron clad guarantees that NATO's jurisdiction or forces would not move eastward" and that it "would have to be done in a manner that would satisfy Germany's neighbors to the east".66 This is ambiguous as to whether he just meant the territory of the GDR or Central and Eastern Europe in general, but the reference to the concerns of “Germany’s neighbors to the east” suggests he was just talking about the GDR. Indeed, if he had been referring to a possible expansion to Central and Eastern European countries, it’s hard to see why those countries would have been concerned about it, whereas it makes perfect sense if he was talking about NATO forces moving into the territory of the GDR, since in that case Czechoslovakia would have to deal with NATO’s presence not just on its western border but also on its northern one and NATO would suddenly appear on Poland’s western border. Although the Warsaw Pact was falling apart, nobody thought it would completely disappear so rapidly, so it made sense to worry about the reactions of those countries.

Baker also proposed a mechanism for the negotiations that would associate the FRG and the GDR to the four powers that still had legal rights over Germany, the so-called "Two Plus Four” mechanism, which eventually became the format under which the negotiations were conducted. Later in the conversation, he suggested that such a mechanism could be used to produce "the right kind of outcome" and went on to say that "it might be an outcome that would guarantee that there would be no NATO forces in the Eastern part of Germany" and even added that "in fact there could be an absolute ban on that". Trachtenberg argues that, since Baker had no problem mentioning the territory of the GDR explicitly in that part of the conversation, it's evidence that, when he used the more ambiguous phrase earlier by assuring Shevardnadze that NATO "would not move eastward" if Germany was allowed to remain part of the Alliance, he was talking about Central and Eastern Europe in general. However, one could argue that, on the contrary, this was a clarification of what he'd meant earlier. The truth is that, just based on what was said during that conversation according to the State Department memorandum that I have been quoting, it's impossible to tell for sure what Baker meant, but I think it’s more likely than not that he was only talking about the GDR. What Shevardnadze understood, on the other hand, is harder to determine.

After his meeting with Shevardnadze, Baker met with Gorbachev and, according to both the State Department memorandum of their conversation and the Soviet record of their meeting, made very similar points and was similarly ambiguous when he talked about not expanding NATO eastward. After explaining why he thought that it would be preferable for everyone, including the Soviet Union, that Germany remain in NATO after reunification, he gave the assurance I already quoted above that in that case the Alliance's jurisdiction would not move "one inch to the east":

We don't favorably view a neutral Germany. The FRG says that this is not a satisfactory approach. A neutral Germany in our view is not necessarily going to be a non-militaristic Germany. It could well decide that it needed its own independent nuclear capability as opposed to depending on the deterrent of the United States. All our allies and East Europeans we have spoken to have told us that they want us to maintain a presence in Europe. I am not sure whether you favor that or not. But let me say that if our allies want us to go we will be gone in a minute. Indeed, if they want us to leave we'll go and I can assure you that the sentiment of the American people is such that they will want us to leave immediately. The mechanism by which we have a US military presence in Europe is NATO. If you abolish NATO there will be no more US presence. We understand the need for assurances to the countries in the East. If we maintain a presence in a Germany that is a part of NATO, there would be no extension of NATO's jurisdiction for forces of NATO one inch to the east.67

In this part of the conversation, Baker is trying to convince Gorbachev that it would actually be in the Soviet Union’s interest to allow Germany to stay in NATO, because otherwise US troops will have to leave the country and Germany will likely become a military power again, which the Soviet Union doesn’t want. He is arguing that German’s continued NATO membership and, relatedly, the US military presence would be a factor of stability in Europe and would therefore benefit the Soviet Union. Again, the phrase Baker used when he said that NATO would not expand is quite general, which if not for the context would be more naturally interpreted as referring to Central and Eastern Europe in general and not just the GDR.

However, the fact that Baker said that immediately after saying that he understood that “countries in the east” would need assurances once again suggests that he was talking about the GDR.68 Indeed, if he was talking about the expansion of NATO to Central and Eastern European countries, then how would ruling out that possibility assuage the security concerns of those same countries? Trachtenberg interprets this passage as evidence that Baker’s assurance was about Central and Eastern Europe in general and not just the territory of the GDR, but that doesn’t make sense since he talked about “countries” in the plural and therefore couldn’t have been referring only to the Soviet Union.69 It’s possible that Baker meant that, if some but not all of them joined NATO, expansion would be seen as a threat to those who stayed outside, but this interpretation seems contrived. It’s much more likely that he was referring to the fact that Central and Eastern European countries, especially Poland which at the time was still worried that after reunification Germany might seek to revise the post-WWII border, would be concerned if NATO suddenly appeared on their borders.70 It’s surprising that, as far I know, no critic of the Russian position has ever made that point, even though it’s a very strong argument in favor of their position that despite the ambiguous language he used Baker was only talking about the GDR.

Still trying to convince Gorbachev that it would be in the Soviet Union's interest to allow Germany to remain in NATO after reunification, he returned to that point later in the meeting:

Baker: I want to ask you a question, and you need not answer it right now. Supposing unification takes place, what would you prefer: a united Germany outside of NATO, absolutely independent and without American troops; or a united Germany keeping its connections with NATO, but with the guarantee that NATO’s jurisprudence or troops will not spread east of the present boundary?

Gorbachev: We will think everything over. We intend to discuss all these questions in depth at the leadership level. It goes without saying that a broadening of the NATO zone is not acceptable.

Baker: We agree with that.71

This comes from the Soviet account of their conversation, but although the State Department memorandum of that meeting is redacted after Baker asks Gorbachev this question, they are virtually identical before that. Moreover, as we shall see shortly, a letter that Baker sent Kohl immediately after the meeting that was declassified by Germany confirms Gorbachev’s reply. Again, they used phrases that were quite general, but still ambiguous in the sense that in this part of the meeting they never explicitly refer to either the territory of the GDR or Central and Eastern Europe in general, so I don't think that we can reach a determination about what they meant or understood the other to be saying just based on the content of this part of the conversation. As before, one can interpret the fact that in other parts of the conversation he specifically mentioned the GDR as evidence that ambiguous phrases about not expanding NATO eastward referred to that, but one can also argue like Trachtenberg that it shows that Baker had no problem mentioning the GDR explicitly when he wanted to make a point specifically about it. Nevertheless, as I argued above, Baker’s reference to Germany’s eastern neighbors earlier in the conversation and during his conversation with Shevardnadze suggests that he was only talking about the GDR.

Robert Gates, Deputy National Security Advisor, met with Vladimir Kryuchkov, head of the KGB, the same day and also tried to convince him that it would be in the Soviet Union's interest to allow a reunified Germany to stay in NATO. In order to make that prospect more attractive to his counterpart, he also said that in that case NATO would not move eastward. Here is how a NSC memorandum of their meeting summarized this part of the conversation:

Events are moving faster than anticipated. We might see some GDR initiative after the 18 March elections. Under these circumstances, we support the Kohl-Genscher idea of a united Germany belonging to NATO but with no expansion of military presence to the GDR. This would be in the context of continuing force reductions in Europe. What did Kryuchkov think of the Kohl-Genscher proposal under which a united Germany would be associated with NATO but in which NATO troops would move no further east than they now were? It seems to us to be a sound proposal.72

As Shifrinson noted, this indicates more support for this idea within the Bush administration than previously recognized.73 On the other hand, since in the first part of his argument Gates apparently talked about not moving NATO forces to the GDR specifically (in contrast to Baker's more ambiguous phrasing), it also suggests that US officials only had in mind a more limited assurance restricted to the territory of the GDR. However, he also refers to Genscher's proposal in the next part of his argument, which as we have seen was not limited to the GDR but applied to Central and Eastern Europe more generally. What Gates meant really depends on whether he saw that proposal as the same as the idea that NATO forces would not move into the territory of the GDR after reunification or as a more general proposal that would just entail the latter. We saw that people in the State Department had noted that Genscher's proposal applied to Central and Eastern Europe more broadly, but it's possible that people in the NSC missed that aspect of the proposal and construed it as more limited than it really was. It's important to keep in mind that governments are not unitary actors, so Gates could have meant one thing and Baker another. In fact, as I’m about to explain, there is evidence that regardless of whether they had noticed that Genscher’s proposal wasn’t limited to the GDR but applied to Central and Eastern Europe in general, people in the NSC were more narrowly focused on the former, so it’s likely that Gates was also talking about the GDR.

Before he went to Moscow, Baker had agreed that he would tell Kohl, who was supposed to meet Gorbachev the next day, what had been said during his conversation with the Soviet leader, so he sent him a letter summarizing their meeting before going back to Washington. In that letter, he used the same language that we have discussed above:

And then I put the following question to him. Would you prefer to see a unified Germany outside of NATO, independent and with no US forces or would you prefer a unified Germany to be tied to NATO, with assurances that NATO's jurisdiction would not shift one inch eastward from its present position.

He answered that the Soviet leadership was giving real thought to all such options, and would be discussing them soon “in a kind of seminar”. He then added: “Certainly any extension of the zone of NATO would be unacceptable.” (By implication, NATO in its current zone might be acceptable.)74

Again, this letter cannot adjudicate the issue of whether this assurance referred only to the territory of the GDR or more generally to Central and Eastern Europe based on this letter, because the language used by Baker remained ambiguous on this point.

In any case, when people in the NSC heard about the question Baker had put to Gorbachev during his meeting with him, they worried that, in his desire to convince the Soviet leader that it was in Moscow's interest to allow Germany to stay in NATO after reunification, Baker might have preemptively made concessions on NATO's future that were not necessary to achieve the US goal of making sure that a reunified Germany would remain in NATO. So the White House drafted and Bush signed another letter to Kohl in which they warned him against making any concessions in advance of express requests by Soviet officials. In that letter, Bush declared himself in favor of a "special military status for what is now the territory of the GDR", but repudiated Baker’s formulation that NATO’s “jurisdiction” would not expand to the east after reunification.75 However, according to Zelikow and Rice, the problem wasn't that Baker's language was ruling out the expansion of NATO to Central and Eastern European countries but that he'd called for no extension of NATO's "jurisdiction" and people in the NSC worried that it would be difficult to reconcile that kind of language with Article 5 of the Washington Treaty, which commits NATO members to mutual defense in case of attack.76 As we shall see, Bush’s formulation is often presented as a hardening of Baker’s proposal, which is true in the sense that it removed any potential ambiguity as to the fact that NATO’s Article 5 would apply to Germany as a whole, including the territory of the GDR. However, the main issue people in the NSC had with his proposal seems to have been, not that it was overly generous, but that taken literally it made little sense, since it seemed to imply that Germany as a whole would be part of NATO yet Article 5 would only apply to some of its territory. Not only would this have been absurd from a political and strategic point of view, but it wasn’t even clear that it could work legally. In any case, after that intervention by the White House, Baker quickly stopped using that kind of language in negotiations with Soviet officials.77 The fact that, in his letter to Kohl, Bush talked specifically about the territory of the GDR and didn’t mention the rest of Central and Eastern Europe is yet more evidence that, despite the ambiguous language they sometimes used in Moscow, US officials were only talking about the GDR.

Thus, right before he met with Gorbachev to begin the negotiations about Germany's reunification, Kohl had received two discordant messages from the US. While Baker talked of the need to give the Soviets assurances that "NATO's jurisdiction would not shift one inch eastward", Bush and the NSC wanted to be clear that NATO would shift to the east of its current position (in the sense that unified Germany as a whole and not just the territory of the FRG would be covered by the Washington Treaty), allowing only for the much smaller concession that after reunification the territory of the GDR would have a "special military status" of some kind. In other words, NATO’s treaty and in particular Article 5 would apply to the entire German territory, even if some restrictions on the Alliance’s freedom of action in the territory of the GDR could be worked out as part of the deal that would allow Germany’s reunification. As Sarotte explains, faced with the choice of which formulation to use in his meeting with Gorbachev, Kohl decided to use "the language most conducive to achieving his goal of German unity" and therefore opted for Baker's formulation.78 As we have seen, this formulation was itself inspired by the language used in the speech Genscher had made in Tutzing and that he'd repeated on several occasions both publicly and privately, but unlike Genscher it seems that Baker never clarified that it applied not only to the territory of the GDR but to Central and Eastern Europe in general and, as I have argued above, it’s very likely that he was only talking about the former.

The Soviet and West German accounts of what Kohl told Gorbachev differ in how specific he was, but according to both, he said that NATO could not expand to the east, instead of using Bush's formulation that NATO would cover even the territory of the GDR, which would simply have a special military status. However, according to the Soviet account of their meeting, Kohl just said that NATO should not "expand its scope of action", whereas according to the West German account he was more specific and said that it "must not extend its sphere to the territory of today’s GDR".79 Kramer claims that "the discrepancy is of negligible importance" since "both transcripts show that Gorbachev would have understood the comment to refer to eastern Germany". Commenting on this discrepancy, Spohr also dismisses it as unimportant, on the ground that "both texts reveal that in delineating NATO’s future boundary the chancellor was referring solely to (eastern) Germany".80 But that is clearly not true, since according to the Soviet but not the German account, what Kohl said was just as ambiguous on that issue as what Baker had said the day before and one cannot conclude that he was only referring to the GDR without begging the question about how to resolve that ambiguity, which is precisely what is at issue here. That being said, since Kohl had read Bush’s letter just before he met with Gorbachev and in that letter the President talked unambiguously about “what is now the territory of the GDR”, I think Kohl likely was only talking about the GDR.

Indeed, while Kohl and Gorbachev were talking, Genscher was having a meeting with Shevardnadze, which Kramer completely ignores, during which he once again gave assurances on NATO expansion that, according to the German memorandum summarizing their conversation, were anything but ambiguous:

Neutralism for Germany as a whole was wrong. We were also thinking of the feelings of our neighbors. It would be better for our neighbors if a united Germany were firmly integrated into European structures. We are aware that NATO membership for a unified Germany raises complicated questions. For us, however, one thing is certain: NATO will not expand to the east. Of course, the newly elected government of the GDR would also have a say in this. It would then have to come to an understanding with the SU. Perhaps it would then turn out that a solution was not so complicated. If Soviet troops remained in the GDR, this was not our problem. The important thing is that we talk to each other in a spirit of trust. As far as the non-expansion of NATO is concerned, this applies in general.81

As you can see, after using the same ambiguous language to assure Shevardnadze that NATO would not expand "to the east", he briefly mentions the GDR to suggest that Soviet troops might be allowed to stay there depending on what the East German government decided, but then goes back to his assurance that NATO would not expand to the east to clarify that it applies "in general".