Summary

A year ago, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit most of the world, there was arguably a good case for lockdowns. The initial growth of the epidemic implied a high basic reproduction number, which in turn meant that unless transmission was reduced the virus would quickly sweep through most of the population because incidence would continue to grow exponentially until the herd immunity threshold was reached, overwhelming hospitals and resulting in the deaths of millions of people in a few weeks. Lockdowns and other stringent restrictions seemed like a plausible way of reducing transmission to "flatten the curve" and prevent that scenario from materializing.

Many people continue to reason along those lines, but since then we have learned that, whatever the precise effect that lockdowns and other stringent restrictions have, it is not so large that it can easily be picked up in the data, as it would surely be if restrictions had the very large effect that pro-lockdown advocates claim. In particular, it is not the case that the alternative to lockdowns is herd immunity (at least in the short run), because in practice incidence never grows exponentially for very long even in the absence of stringent restrictions. While it is plausible that, without stringent restrictions, incidence would start falling a bit sooner and faster, the data show very clearly that it always starts falling long before the herd immunity threshold is reached with or without a lockdown.

Many factors likely contribute, but the main explanation of that fact is probably that, despite what simple epidemiological models assume, people modify their behavior in response to changes in epidemic conditions such as rising hospitalizations and deaths, which reduces transmission and causes the epidemic to recede long before the herd immunity threshold is reached. However, until enough people have acquired immunity through natural infection or vaccination, this is only temporary and eventually incidence starts growing again because people go back to more regular behavior. Lockdowns and other stringent restrictions do not have a very large effect because they are a blunt instrument and have a hard time targeting the behaviors that contribute most to transmission.

The belief that lockdowns are very effective nevertheless persists because authorities react to the same changes in epidemic conditions as the population, so they tend to implement lockdowns and other stringent restrictions around the time when people start modifying their behavior. This means that the effect of voluntary behavioral changes is attributed to lockdowns even if the epidemic would have started to recede in the absence of stringent restrictions. We know this because that is exactly what happened in places where the authorities did not put in place such restrictions, which are extremely diverse economically, culturally and geographically and therefore unlikely to share some characteristics that allow them to reduce transmission without a lockdown.

Places where the virus seems to have spread more are those where the population is relatively young, which is exactly what the theory presented here–that voluntary behavioral changes in response to changes in epidemic conditions are the main driver of the epidemic–predicts, since a younger population implies a lower rate of hospitalization and death, which in turn means that the virus will have time to spread more before the rise in hospitalizations and deaths scare people into changing their behavior enough to push the reproduction number below 1.

The scientific literature on the effect of restrictions on transmission contains many inconsistent results, but more importantly it is methodologically weak and therefore completely unreliable. To be sure, many studies found that restrictions had a very large effect on transmission, which pro-lockdown advocates like to cite. However, those results do not pass a basic smell test since one just has to eyeball a few graphs to convince oneself the studies they come from perform terribly out of sample, which is not surprising since most of them either assume that voluntary behavior has no effect whatsoever on transmission or do not use methods that can establish causality by disentangling the effect of restrictions from that of voluntary behavior changes.

Even if you make completely implausible assumptions about the effect of restrictions on transmission, and ignore all their costs except their immediate effect on people's well-being, they do not pass a cost-benefit test. For instance, in the case of Sweden (where incidence is growing again and the government is considering tightening restrictions), if you assume that a lockdown would save 5,000 lives (which is approximately the total number of deaths during the first wave, when the population was behaviorally naive and vaccination was not under way), a 2-month lockdown followed by a gradual reopening over the next 2 months would have to reduce people's well-being by at most ~1.1% on average over the next 4 months in order to pass a cost-benefit. In other words, for a lockdown to pass a cost-benefit test under those assumptions, you would have to assume that on average people in Sweden would not be willing to sacrifice more than ~32 hours in the next 4 months to continue to live the semi-normal life they currently enjoy instead of being locked down.

While I use Sweden to illustrate my point because it has been a focal point of the debate about restrictions, this exercise yields a similar conclusion almost everywhere else. The truth is that, from a cost-benefit perspective, Sweden's much-decried strategy has been vastly superior to what most Western countries have done and it is not even close. Even if you think that it would have been better for Europe and the US to follow Australia and New Zealand's example by adopting a so-called "zero COVID" strategy after the first wave, which would probably not have succeeded anyway even back then, this boat has already sailed and trying to pull it off now makes absolutely no sense from a cost-benefit perspective. Despite popular but confused arguments to the contrary, which I discuss at the end of this essay, this remains true even if you take into account the threat posed by new variants of SARS-CoV-2.

Almost every country in the world has now gone through 2 or 3 waves of the COVID-19 pandemic and, in most of them, incidence remains high although it has recently been falling almost everywhere. everywhere. Although the vaccine is being rolled out in many places, it is at a very slow pace with most countries facing shortage and distribution problems. This means another flare-up is likely in many places even if the worst of the pandemic is probably behind us. While lockdowns and other stringent restrictions had high levels of support when the first wave hit, this is no longer true and, as we are entering the last phase of the pandemic, the debate about how to deal with it has never been so intense. Sweden went a different route last spring by foregoing a lockdown and, while it remains widely vilified for this decision, even some people who thought it was a mistake at the time have changed their mind and now think other countries should follow Sweden’s example and seek to contain the epidemic without stringent restrictions such as stay-at-home orders, outright business closures, etc.

I’m one of them. Back in spring, I was in favor of lockdowns, but since then I have reached the conclusion that lockdowns and other stringent restrictions do not make sense from a cost-benefit perspective. I now think that, even with the information we had at the time, supporting lockdowns was the wrong call because even though I insisted that it was only a temporary solution and that we should be ready to revise our view as more evidence came in, I should have known that people would not and that lockdowns would quickly become institutionalized. However, in this post, I will not be arguing for this view. I only want to argue that, regardless of what should have been done last spring, the data we have accumulated since then show very clearly that, whatever the precise effect of lockdowns and other stringent restrictions, it is not nearly as large as we might have thought, so their costs far outweigh their benefits and we therefore should avoid them where they are not currently in place and start lifting them immediately where they are.

Back in March, there was at least a case in favor of lockdowns. Indeed, we didn’t know at the time how difficult it would be to reduce transmission, but we knew that R_0 had been measured at ~2.5 and that in most countries thousands of people were already infected, which meant that unless transmission was reduced quickly more than 90% of the population might be infected in a few weeks. Since the evidence suggested that the infection fatality rate (IFR) was around 1% even when people received proper treatment, this in turn meant that in a country like the United States, between 2 and 3 million people would die even if hospitals were not overwhelmed. However, if the virus swept through the majority of the population in a few weeks, the hospitals undoubtedly would be, so most people would not receive proper care, the IFR would consequently rise way above 1% and the number of deaths would actually be much higher. A lockdown would cut transmission and, while it could not prevent a large part of the population from getting infected eventually, because we couldn’t stay locked down forever, it would “flatten the curve” and prevent hospitals from being overwhelmed and the rise of the IFR this would cause.

But while this line of thought was reasonable at the time, it has become clear that it rested on a flawed premise. Even without a lockdown and stringent restrictions, incidence always starts falling long before the herd immunity threshold is reached. In fact, not only are lockdowns and other stringent restrictions unnecessary to prevent the virus from ripping through most of the population in a few weeks, but they don’t seem to be making a huge difference on transmission. This makes a more liberal approach, not unlike what Sweden has done, far more appealing from a cost-benefit perspective and should have radically altered the policy debate. Unfortunately, this has largely not happened, because most people still believe the flawed assumptions of the original argument for lockdowns and have kept moving the goalposts. At any rate, this is the case I will make in this post.

The alternative to lockdowns and other stringent restrictions is not herd immunity

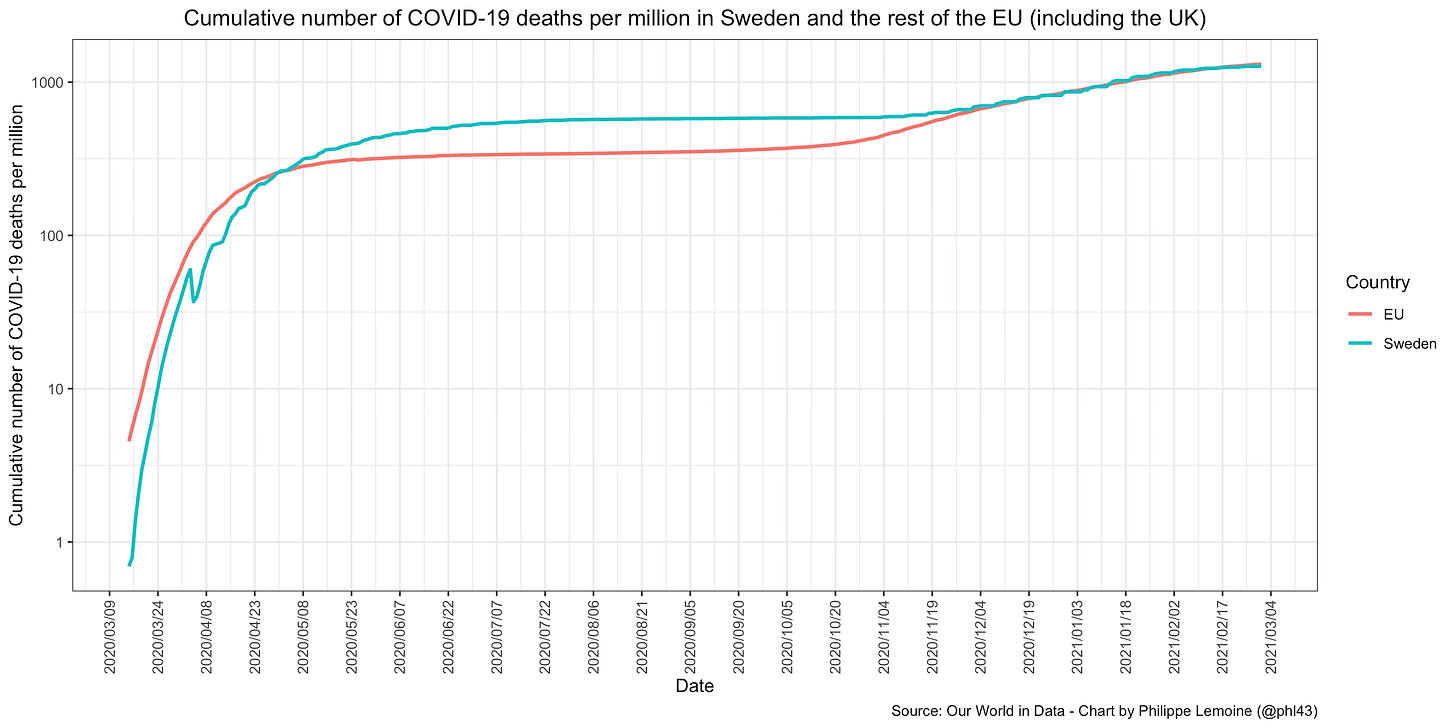

The first thing everyone should acknowledge at this point, although many people still don’t, is that whatever the precise effect of lockdowns and other stringent restrictions is, it can’t be huge. In particular, it’s certainly not the case that, in the absence of a lockdown, the virus quickly sweeps through the population until the epidemic reaches saturation. There is no need for anything fancy to convince yourself of that, you just have to eyeball a few graphs. Here is my favorite:

As you can see, Sweden was ahead of the rest of the EU after the first wave, but the rest of the EU has caught up since then and now the number of COVID-19 deaths per capita in Sweden is about average.

Of course, policy is not the only factor affecting the epidemic (that’s the point), so this graph does not show that lockdowns and other stringent restrictions have no effect, but if policy mattered as much as pro-lockdown advocates claim, it would look completely different. Indeed, although Sweden has tightened restrictions to fight the epidemic in recent months and the other EU countries have on the contrary used less stringent restrictions during the second/third wave, restrictions in Sweden remain much less stringent than almost everywhere else in Europe and this was already true during the first wave. In particular, even if they have to close earlier and respect stricter health regulations, bars and restaurants are still open and there is no curfew. If lockdowns and other stringent restrictions were really the only way to prevent the virus from quickly sweeping through the population until saturation is reached, the number of deaths per capita in Sweden would be 3 to 15 times higher and that graph would look very different. Yet people continue to talk as if lockdowns were the only way to prevent that from happening. In fact, as we shall see, most scientific papers about the effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions implicitly rest on that assumption. It’s as if reality didn’t matter, but it does, or at least it should.

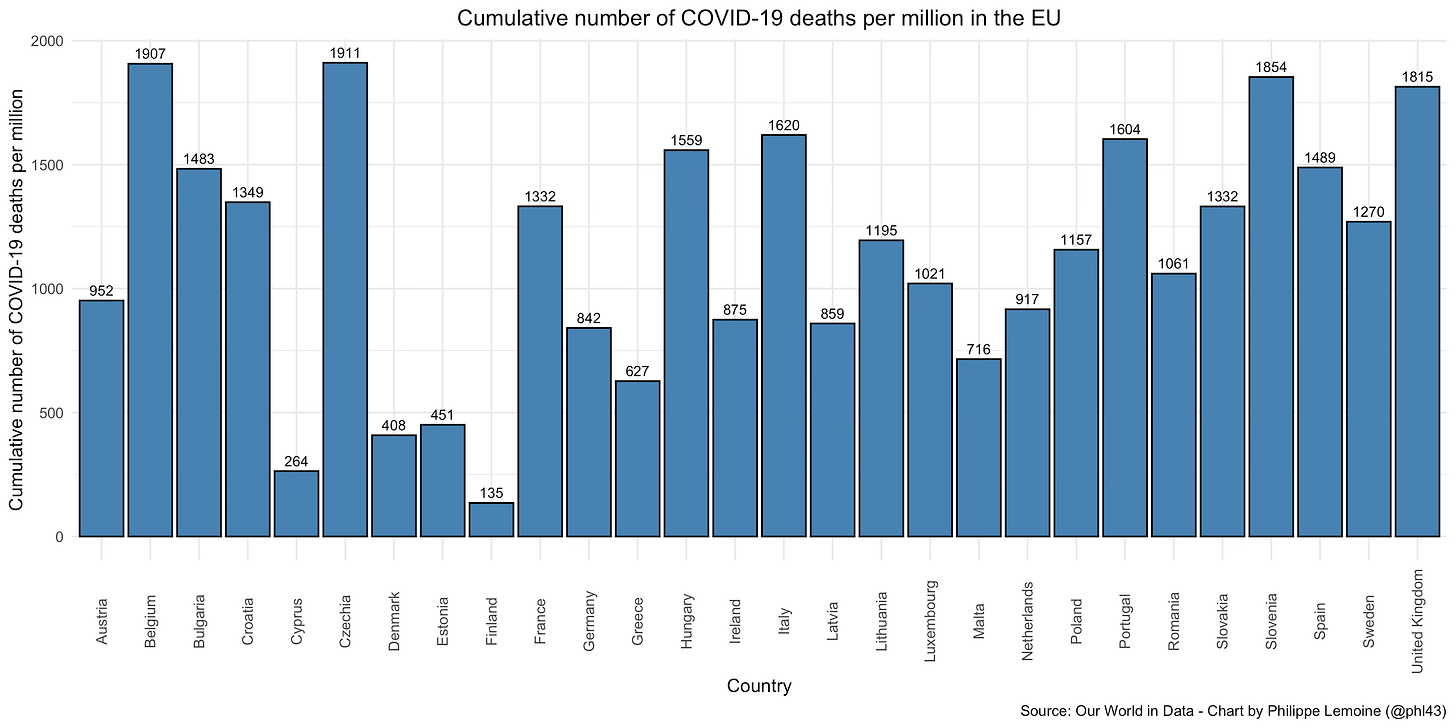

The average number of COVID-19 deaths per capita for the EU without Sweden hides a significant amount of heterogeneity:

However, as you can see, the picture remains very similar even when you disaggregate and still shows a lot of convergence.

Moreover, although there remain significant disparities between EU countries, what is striking, if you have kept yourself informed about the various policies used to contain the epidemic in various EU countries, is the lack of any clear relationship between policy and outcomes:

For instance, Finland is the country with the smallest number of COVID-19 deaths per capita, yet although it locked down last spring, restrictions in Finland have been even more relaxed than in the much-reviled Sweden for months. Of course, I’m not saying that you couldn’t find some kind of relationship if you looked close enough and used enough fancy statistics, but the point is precisely that you’d have to look very close.

The situation is very similar in the US. You may recall that, back in April, The Atlantic published a piece called “Georgia’s Experiment in Human Sacrifice“ decrying the decision by the governor of that state to lift many restrictions. So let’s have a look at the result of this so-called experiment:

As you can see, the number of COVID-19 deaths per capita did increase and eventually caught up with the average of the US (although this graph doesn’t show any clear effect of Governor Kemp’s decision to lift many restrictions at the end of April), but the carnage predicted by opponents of that decision never happened and the number of COVID-19 deaths per capita in Georgia is actually slightly under the US average. Again, Georgia may have characteristics that protected it from a worse outcome and this graph obviously doesn’t show that the death toll would not have been lower with more stringent restrictions, but it still makes clear that policy isn’t as powerful a factor as Kemp’s critics assumed and as many people still assume.

As in the case of the EU, if you disaggregate, the graph reveals a lot of heterogeneity between states, but the same pattern of convergence is also present:

Some of the states that were relatively spared during the first wave remain less affected than average, but the difference has shrunk and, in many other cases, they have caught up with the US average and sometimes even exceed it.

Again, although there remain significant disparities between states, the role of policy doesn’t jump out at you if you know what different states have done to deal with the pandemic:

Again, I’m not saying that you couldn’t find a relationship with policy if you looked hard enough, but it would take some work and no amount of statistics should convince anyone who has seen those graphs that lockdowns and other stringent restrictions are the only way to prevent the virus from quickly sweeping through the population until saturation is reached.

Even if someone has been able to find a large effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions on transmission with a more sophisticated statistical analysis, the fact it doesn’t jump at you when you look at this kind of simple graphs should make you skeptical of that finding and, the larger the effect, the more skeptical you should be, because if non-pharmaceutical interventions really had a very large effect it should be easy to see it without fancy statistics. I think that, in general, one should be very suspicious of any claim based on sophisticated statistical analysis that can’t already be made plausible just by visualizing the data in a straightforward way. (To be clear, this doesn’t mean that you should be very confident the effect is real if you can, which in many cases you shouldn’t.) That’s because sophisticated statistical techniques always rest on pretty strong assumptions that were not derived from the data and you should usually be more confident in what you can see in the data without any complicated statistical analysis than in the truth of those assumptions. So visualizing the data provides a good reality check against fancy statistical analysis. By following this principle, you will sometimes reject true results, but in my opinion you will far more often avoid accepting false ones. As we shall see later, not only is the literature on the effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions no exception, but it’s actually a great illustration of the wisdom of that principle.

Another way to convince yourself that, whatever the precise effect of lockdowns and other stringent restrictions, it’s almost certainly not huge is to compare the timing of non-pharmaceutical interventions with the evolution of the epidemic. Indeed, while you can find plenty of examples that are compatible with the pro-lockdown narrative, as long as you don’t cherry-pick the data, you can also find plenty of examples that are difficult to reconcile with that narrative. In particular, if you look at the data without preconceived notions instead of picking the examples that suit you and ignoring all the others, you will notice 3 things:

In places that locked down, incidence often began to fall before the lockdown was in place or immediately after, which given the reporting delay and the incubation period means that the lockdown can’t be responsible for the fall of incidence or at least that incidence would have fallen even in the absence of a lockdown.

Conversely, it’s often the case that it takes several days or even weeks after the start of a lockdown for incidence to start falling, which means that locking down was not sufficient to push R below 1 and that other factors had to do the job.

Finally, there are plenty of places that did not lock down, but where the epidemic nevertheless receded long before the herd immunity threshold was reached even though incidence was increasing quasi-exponentially, meaning that even in the absence of a lockdown other factors can and often do cause incidence to fall long before saturation.

I’m just going to give a few examples for each category, but I could talk about many others in each case and, if you spend a bit of time looking at the data, you will have no problem finding more yourself.

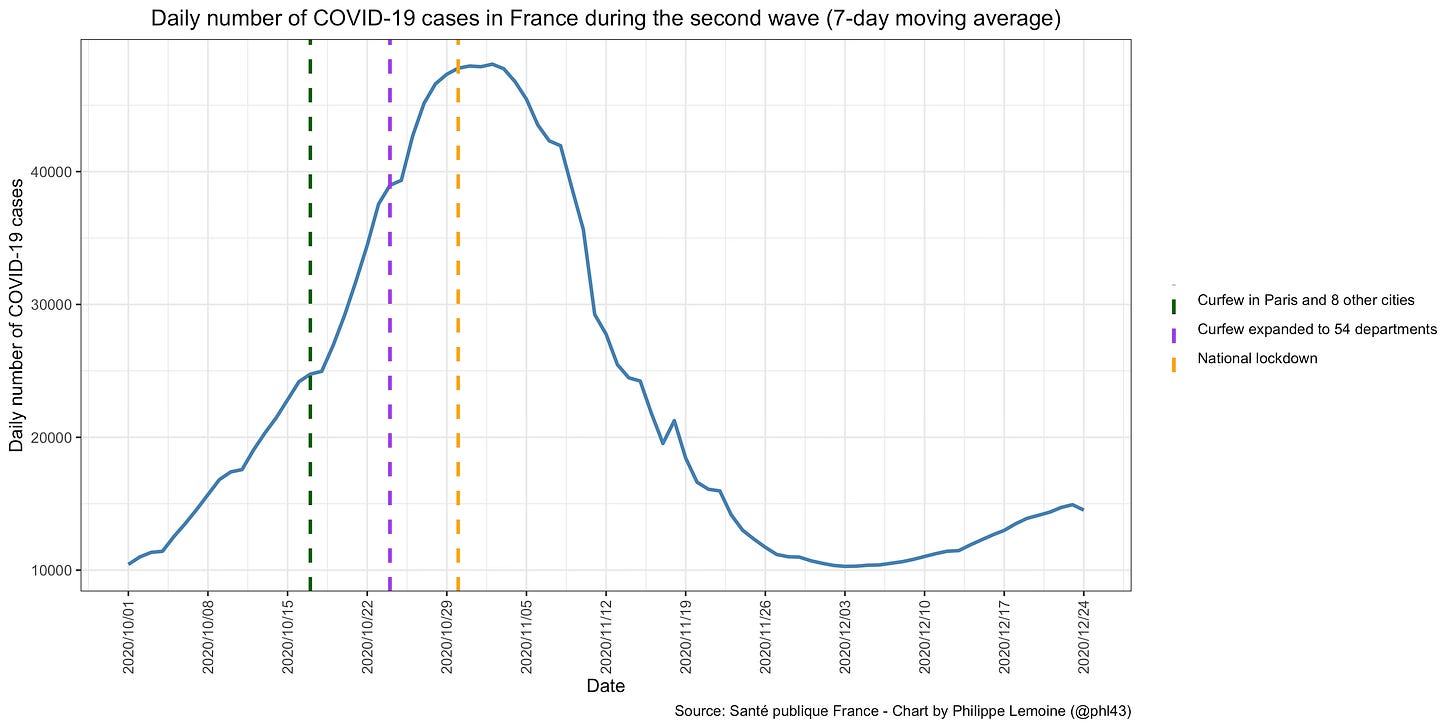

A good example of a place where incidence started falling before the lockdown was in place is France during the second wave:

We can see clearly that had already stopped increasing by the time the lockdown came into effect.

Since the incubation period lasts almost a week on average and people generally don’t get tested immediately after the onset of symptoms, there is absolutely no way the fall of incidence was due to the lockdown, although we can’t exclude that it accelerated the fall once it came into effect. Indeed, when you infer the number of infections from the data on death by using the infection-to-death distribution to reconstruct when people were infected based on when they died, you find that the peak was reached about a week before the lockdown started, even without taking into account the reporting delay in the data on deaths. This method is not very precise and the specific date of the peak shouldn’t be taken seriously, but it’s clear that incidence started falling before the lockdown. This is so obvious that it’s clear even in all-cause mortality data, which have the inconvenience of not including only deaths due to COVID-19, but the benefit of being higher-quality since deaths are recorded by date of death and not by date of report.

Yet another way to see that is to disaggregate the data geographically and look at different areas separately. For instance, if you look at the number of cases in Paris, you can clearly see that incidence started falling before the lockdown:

As you can see, by the time the lockdown came into effect, incidence had already been falling for a few days. You could argue that it’s because of the curfew, though it’s unclear the timing is consistent with that hypothesis either and there are regions where incidence started falling before the lockdown despite the absence of curfew, but in any case it’s definitely not because of the lockdown.

Unfortunately, being as clueless as ever, the epidemiologists who advise the French government still don’t seem to have gotten the memo even 4 months later. Indeed, in a paper they recently published about machine learning models they created to predict the short-term evolution of the epidemic, they note that all of them “over-estimate the peak since the lockdown”, but claim it’s because the date of the lockdown “could not have been anticipated”, which is obviously not the explanation since again the peak of infections was reached before the lockdown. If you take another look at the graph for the country as a whole, it’s also interesting to note that incidence started to rise again about 2 weeks before the lockdown was lifted on December 15. You can say that it’s because people started to relax and this reduced compliance, but you don’t actually know that and, even if that were true, it’s the effectiveness of the actual lockdown that we’re interested in, not a theoretical lockdown where compliance remains the same throughout. Indeed, you can’t ignore the problem of non-compliance, which becomes even more important as time goes by and “lockdown fatigue” sets in.

The UK during the second wave also provides a very interesting example, even though it’s not clear that incidence started falling before the second national lockdown started on November 5. Indeed, the Office for National Statistics has been conducting the COVID-19 Infection Survey, a repeated cross-sectional survey of SARS-CoV-2 swab-positivity in random samples of the population since last May, so we have much better data to follow changes in incidence than in other countries, where we have to rely on data on non-random tests that are extremely noisy and subject to various biases. Here is a chart from the December 11, 2020 report, which shows the proportion of people in England that tested positive in that survey:

If you look at the point estimates, the peak was reached during the week between November 8 and November 14, but the confidence intervals of the estimate overlap for any week between October 17 and November 21, so we can’t rule out the hypothesis that it was reached before the lockdown started. But regardless of when exactly the peak was reached, what is certain from this graph is that the growth rate of positivity started to collapse long before the lockdown started, so there is every reason to believe that incidence would have fallen even without a lockdown.

If you look at the results disaggregated by region in the same report, it does look as though positivity started to fall before the lockdown in some regions:

However, since a three-tiered framework of restrictions had been introduced in October, it could be argued that the decline in positivity was due to the restrictions that were implemented in those regions before the lockdown came into effect. (The same thing could be said about France during the second wave, where a curfew was put in place in some regions before a national lockdown was implemented.) What is more interesting is that, in several regions, the lockdown is not clearly associated with any change in positivity, which is hard to reconcile with the hypothesis that lockdowns and stringent restrictions have a very large effect. Although those results involve a lot of modeling and shouldn’t be taken at face value, this is another thing that we see again and again in the data of several countries when they are disaggregated by region, which has been largely ignored even though, or perhaps because, it’s at odds with the pro-lockdown narrative.

Next, let’s move to the second type of phenomenon I identified above, namely places where a lockdown was implemented but wasn’t associated with any fall of incidence. The most striking example of that phenomenon is arguably Peru, which had the worst epidemic in the world despite locking down very early:

Pro-lockdown advocates like to insist that lockdowns are most effective when they are done early and the rules are stringent. Peru went on lockdown merely 9 days after the first case and before anyone had even died of COVID-19. Moreover, with the exception of China, the rules were stricter than anywhere else in the world and the government tightened them several times during the first 2 weeks of the lockdown. At one point, only men were allowed to leave their home on certain days and only women the rest of the week, while nobody was allowed to do so on Sunday. Grocery stores had to close at 3pm and the military was patrolling the streets to enforce the curfew. If there is one country where a lockdown should have prevented the epidemic from getting out of control, it was Peru, but it instead had the world’s highest known excess mortality rate in 2020.

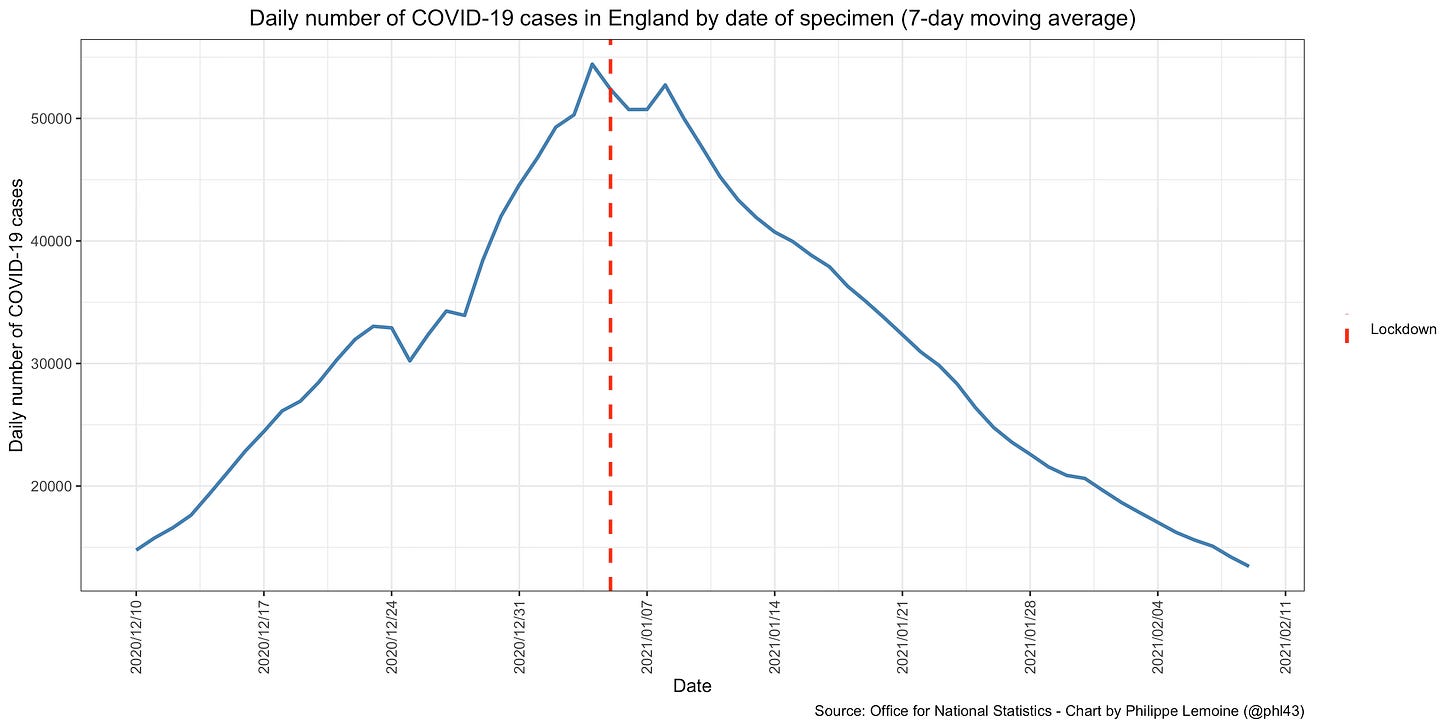

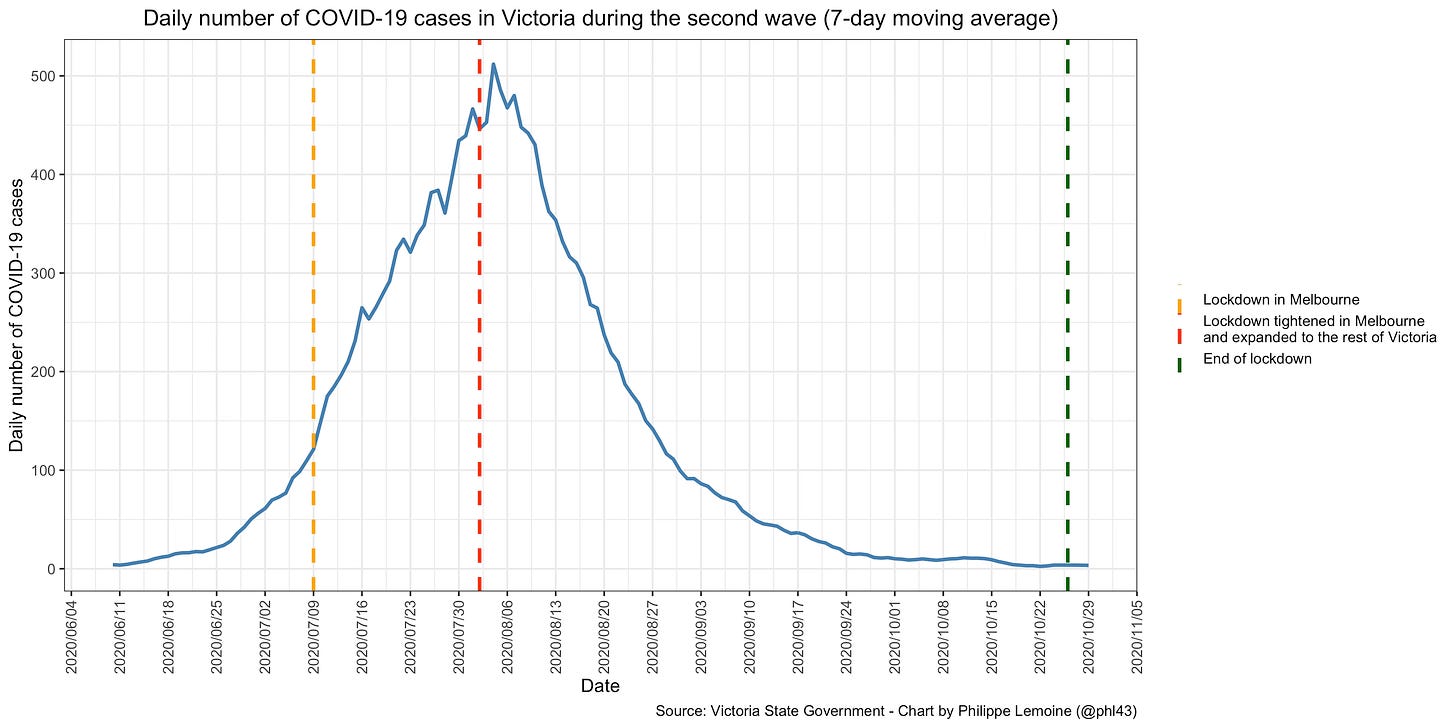

There are other examples of lockdowns that didn’t show any clear effect. Ironically, one of them is the lockdown in Melbourne that started in July and is often cited as an example by proponents of the so-called “zero covid” strategy, but I will discuss that later. Rather than look at clear-cut examples, I would like to discuss the third national lockdown in the UK, which is a very interesting case because, depending on what data you look at, you can argue that incidence started to fall immediately after it came into effect, that it started to fall before that or that it didn’t start to fall until much later. Thus, it illustrates the danger of inferring that a lockdown “worked” by visually inspecting a chart that shows the daily number of cases and noticing that it started falling shortly after the lockdown came into effect, as pro-lockdown advocates constantly do. Indeed, if you look at a graph showing the daily number of cases in England during the third wave, it certainly looks as though the lockdown worked exactly as expected:

As you can see, the daily number of cases peaked a few days after the lockdown came into effect, which given the average incubation period seems roughly consistent with the hypothesis that transmission was suddenly cut by the lockdown.

This is the graph most pro-lockdown advocates are looking at and the inference they make, but it doesn’t account for the reporting delay, which pushes back further the time when incidence started falling. Fortunately, the Office for National Statistics also publish data on the number of cases by date of specimen, so we can plot the daily number of cases without the reporting delay:

As you can see, this tells a different story, since it shows that the number of cases actually started falling a few days before the lockdown came into effect. Since the incubation period lasts almost a week on average and people generally don’t get tested immediately after symptoms onset, this suggests that the number of infections started to fall at least a week before the lockdown came into effect, which would make England during the third wave another example of the first type of phenomenon I identified above.

Remarkably, when you disaggregate and look at the same data by region, every region exhibits a very similar pattern:

This is remarkable because, on December 19, new restrictions were applied to London and parts of the East and South East that in some ways prefigured the lockdown, so if stringent restrictions had a large effect you would expect to see more pronounced differences between regions. It does look as though infections started to fall a little bit sooner and then fell a little bit faster in the regions where more stringent restrictions were in place, but the effect is hardly impressive and, as I will explain later, the results doesn’t mean that it was causal and there are good reasons to doubt that it was.

But things are even more complicated with the third national lockdown in the UK. Indeed, while it looks as though incidence started to fall before the lockdown came into effect when you look at the data on cases, the REACT-1 study, another repeated cross-sectional survey of SARS-CoV-2 swab-positivity in random samples of the population of England whose 8th round was conducted in the 2 weeks following the beginning of the lockdown, didn’t find any fall in the positivity rate immediately after the lockdown started:

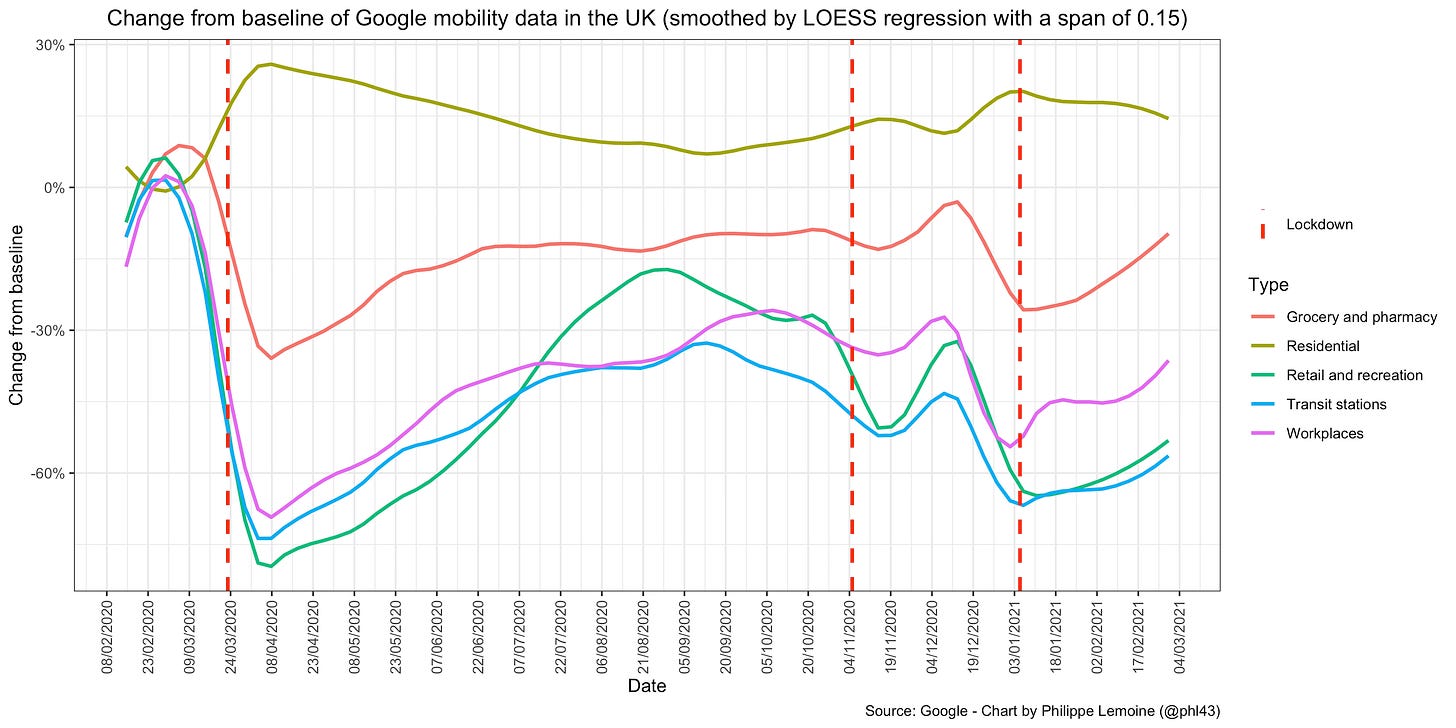

As you can see, the positivity rate didn’t start falling until January 16, more than 10 days after the lockdown came into effect. Even taking into account the time it takes between the moment someone is infected and the moment the virus has replicated enough for a PCR test to come back positive, this seems too late for the lockdown to explain it. The authors of the report suggests that it may be due to a temporary increase in household transmission driven by the start of lockdown, as people started to spend more time with their family, but this is merely a conjecture and, as the report also notes, data on mobility don’t show any effect of the lockdown.

The results disaggregated by region are once again show a diversity of patterns that is hard to reconcile with the hypothesis that restrictions have a huge effect on transmission:

As you can see, in most regions the positivity rate doesn’t seem to have decreased much or at all even 2 weeks after the beginning of the lockdown, except in South West where robustly decreasing prevalence can be observed and East Midlands where prevalence actually seems to have increased during that period. I don’t see how anyone can look at those data and conclude that the lockdown was the main factor driving the epidemic in England during that period, which is probably why pro-lockdown advocates generally ignore them.

The COVID-19 Infection Survey also found a great deal of heterogeneity in the trajectory of the positivity rate in different regions, which is not what you’d expect if the lockdown had a massive effect on transmission:

It’s also remarkable that, in several regions, the results are strikingly different from what the REACT-1 study shows. Of course, the results are not straightforwardly comparable, if only because the COVID-19 Infection Survey uses a different modeling approach. But the fact that you can get such different results is still pretty telling, because if the lockdown really had the kind of massive effect that pro-lockdown advocates claim, not only would you see a more homogenous response across regions, but differences in modeling choices presumably wouldn’t result in such inconsistent results.

But what’s even more striking is that data from repeated cross-sectional surveys of SARS-CoV-2 swab-positivity in random samples of the population tell a completely different story from data on cases, which as we have seen suggest that incidence started falling everywhere about a week before the lockdown started. There are many possible explanations for this apparent inconsistency. For instance, it could be that infections started to fall earlier among older people, who are more likely to be symptomatic and get tested, but continued to increase among younger people for some time. However, this is not what the data from the COVID-19 Infection Survey show, so it probably isn’t the explanation. Another possible explanation is that data from the REACT-1 study and the COVID-19 Infection Survey, even though they rely on random samples of the population, are not very good. Indeed, the response rate seems pretty low in both cases, so inferring the prevalence of infection in the population from the sample may be misleading. Moreover, testing by PCR can detect viral RNA in swabs for a while after the infection was successfully fought off by the immune system, which probably makes it difficult to pick up small, gradual changes in prevalence even in a large sample. Of course, the problem could still come from the data on cases, it’s possible that something other than age changed among the people who were infected that resulted in a fall of the number of cases even though the number of infections was still increasing or staying roughly constant.

I spent some time on the case of the third national lockdown in England because it illustrates that, even when it looks as though a lockdown is clearly working, things get a lot muddier when you take a closer look at the data. The case of England is particularly interesting because, unlike in many places where only the data on the number of cases by date of report are available, we have lot of different sources of data on the epidemic in England, but I’m sure we’d reach a similar conclusion elsewhere if we had more data. The truth is that, based on the data we have, it’s impossible to tell whether the number of infections started to fall before, shortly after or as late as 10 days after the lockdown came into effect. Note that I’m just talking about what we can tell about the timing of the epidemic relative to that of the lockdown here, but as I will explain later, we couldn’t infer that the lockdown was responsible even if we knew for sure that incidence started to fall shortly after it came into effect, so the pro-lockdown case is even weaker than it looks. In general, I hope this discussion has illustrated how incredibly noisy the data about the pandemic are, even in the UK which has much better data than virtually any other country. This is important because all the studies that people tout as proof that lockdowns and other stringent restrictions have a huge effect on transmission are based on such very low-quality data, but I will go back to the scientific literature on the effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions later.

For the moment, I would like to turn to the third type of phenomenon I identified above, namely places that didn’t lock down but where incidence nevertheless started falling after a period of quasi-exponential growth. Examples of this type are for me the most important because they show that, even without a lockdown and with far less stringent restrictions than those currently in place in France and many other countries, a phase of quasi-exponential growth of incidence never lasts very long and the epidemic always ends up receding long before the herd immunity threshold is reached. The best known example is of course Sweden, which has never locked down and where restrictions are much less stringent than almost anywhere else in Europe, but where incidence didn’t continue to increase exponentially until the herd immunity threshold was reached but actually started to fall way before that, be it during the first wave last spring or during the second wave this winter:

The data on cases are misleading for the first wave, because Sweden was testing very little at the time, so it looks as though incidence remained low, but the data on ICU admissions show very clearly that’s not what happened. What is also clear is that, despite the lack of lockdown or very stringent restrictions, the epidemic quickly reached its peak and began to decline by the beginning of April. For the second wave, Christmas and New Year’s Day clearly affected the data on cases, but we can still see that incidence declined for several weeks starting from the end of 2020 (even though it recently started to increase again), a conclusion that is further strengthened by the data on ICU admissions. As during the first wave, the epidemic eventually receded without a lockdown or a curfew and while small businesses, bars and restaurants remained open, even though the sale of alcohol is prohibited from 8pm onwards and a number of restrictions are still in place.

Many people think that Sweden is unique, but that’s not the case at all, there are many other places beside Sweden that have not locked down and where the epidemic still ended up receding long before saturation. For example, it’s what happened in Serbia this fall, where there was no curfew and bars and restaurants remained open during the week even at the height of the second wave, even though they had to close earlier than usual on weekdays and completely on weekends:

Again, it’s not as if there were no restrictions in Serbia, but they are much less stringent than in France and most other European countries. However, this didn’t prevent the epidemic from receding, even though it is clear that the country is very far from having reached the herd immunity threshold. Recently, incidence started increasing again, but it does not change what happened before and this is perfectly consistent with the explanation I will propose in the next section.

In the US, many states also refused to lock down after the first wave, but that didn’t stop the epidemic from eventually receding everywhere. For instance, this is what happened in Florida, one of the most populous states in the US, both last summer and this winter:

I also show the daily number of deaths because, like everywhere else, Florida tested very little during the first wave and the data on cases are therefore misleading.

Florida did lock down in April, but since then Ron DeSantis, the state’s governor, has refused to do it again. Even at the height of the second wave, bars and restaurants remained open and there was no curfew except in Miami-Dade County, although the sale of alcohol was banned in bars at the end of June. In September, the governor ordered that all health restrictions be lifted in bars and restaurants, prohibiting even counties and cities from imposing such restrictions locally, which did not result in a resurgence of cases. When incidence began to rise again in November, despite the fact that experts and the media demanded that he impose stringent restrictions again, he refused to give in and the state remained completely open. Nevertheless, as you can see on the graph, the third wave also started to recede at the beginning of the year and incidence in Florida has been steadily falling since then. While there have been almost no restrictions since September, which actually makes Florida a far more extreme counter-example to the pro-lockdown narrative than Sweden, the cumulative number of deaths per capita in that state is barely higher than in France, where there is a curfew of 6pm, bars and restaurants have been closed everywhere since the end of October, etc. One could make a similar comparison with other European countries where restrictions have been very stringent or, as we shall see, with California, where restrictions are also far more stringent and where there even was a lockdown.

I could go on like that for hours, because there are plenty of examples that contradict the claim that, without a lockdown, incidence continues to rise quasi-exponentially until the herd immunity threshold is reached. Not only is this patently false, but in developed countries at least (I will go back to this point below), the epidemic ended up receding long before that point in every place that did not lock down, without a single exception. Unfortunately, most people don’t know that, because there is a huge bias in the way the media and people on social networks talk about the pandemic. For example, as long as the incidence was rising very rapidly in Sweden, I would see graphs every day showing the explosion of cases accompanied by alarmist and/or sarcastic commentary about the Swedish strategy, but curiously since incidence started falling I don’t hear about Sweden anymore. It’s the same thing with Florida, North Dakota, South Dakota, Georgia and every other place that did not lock down and where almost everything remained open even at the height of the second and/or third waves. Similarly, almost nobody has ever heard about what happened in Serbia, which adopted a strategy very similar to that of Sweden during the second wave.

Conversely, when a lockdown or stringent restrictions fail to quickly produce visible results, as in California last December, you don’t hear from that place again until incidence finally starts falling, which again it always does eventually with or without a lockdown or stringent restrictions. At which point, you start hearing about that place again, which becomes the latest proof that lockdowns are effective even though it’s hardly obvious upon taking a close look at the data, as we have seen in the case of the third national lockdown in England. When a lockdown has failed to produce any visible results even after 2 weeks, but the media can’t ignore it for one reason or another, we are assured that it’s because it wasn’t strict enough. Of course, pro-lockdown advocates never say in advance what restrictions will be stringent enough, nor after how long we may conclude that they didn’t work, so they can never lose.

When incidence starts rising again in places that have not locked down, which will probably happen in at least some of them, the same people who had forgotten their existence will start talking about the “Swedish disaster“ or the “Georgia’s experiment in human sacrifice“ again. Cases that support the view that only very stringent restrictions can prevent a disaster are talked about constantly, while any counter-example to that view is systematically ignored. For the most part, people are not even being intellectually dishonest, it’s just confirmation bias on steroids. This is made worse by the fact that the issue has been politicized, though not always along traditional political divides, so people have to toe the party line. I know many people who understand what I’m saying perfectly well, but they will never say it publicly or say it in a much watered down form, because they’re afraid of what people on their team would think. The issue of lockdowns has practically become a religion for some people and they do not easily forgive slights to their god.

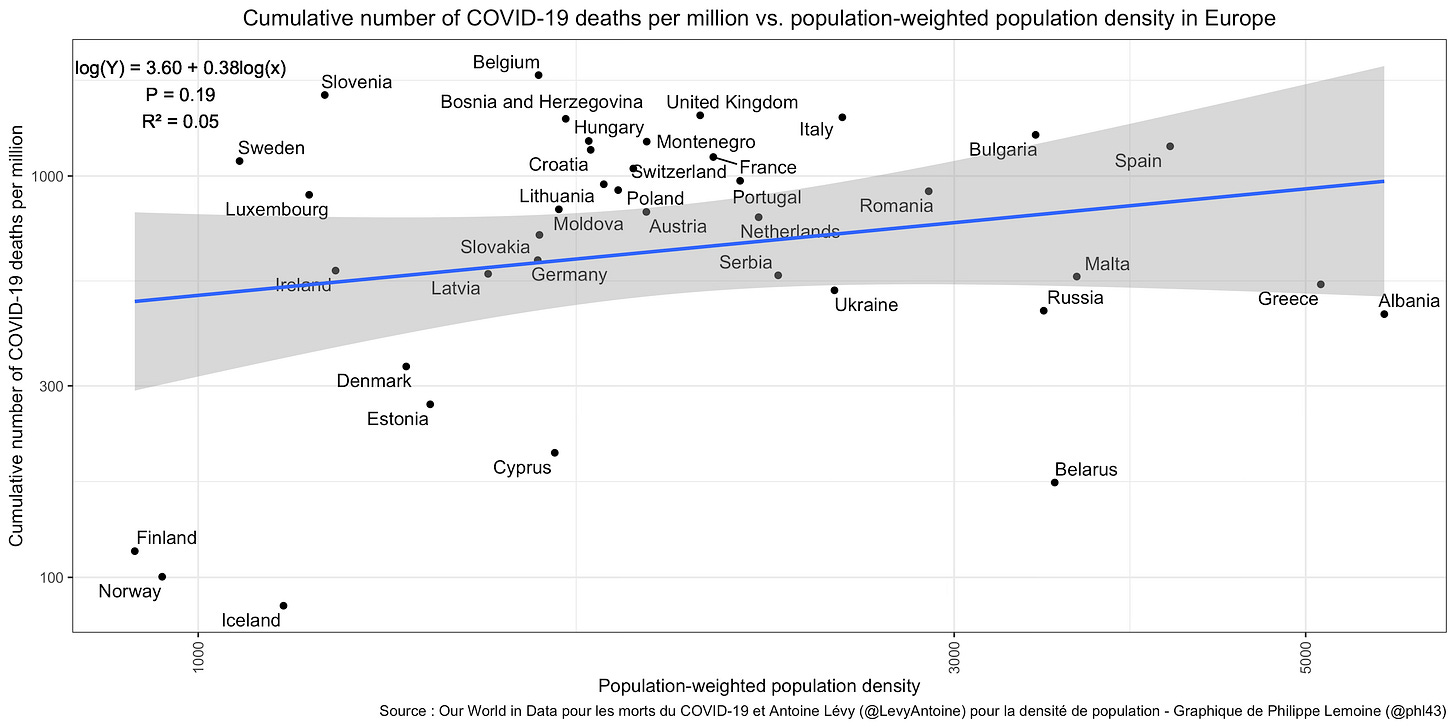

When you point out counter-examples to their view, pro-lockdown individuals always have a way to explain them away. They are always ready to bring up a difference, real or imagined, between places that have not locked down and others that did not which they believe explains why the epidemic wasn’t significantly worse in the former than in the latter. In the case of Sweden, what always comes up is population density. If Sweden did not have more COVID-19 deaths than many countries that have put in place far more stringent restrictions, so the argument goes, it’s because it has a very low population density. The problem is that, when you look at the data, there is no clear relationship between population density and the number of COVID-19 deaths per capita:

I have restricted myself to Europe, which is relatively homogeneous in demographic and economic terms, to reduce the risk that even a strong association between population density and the number of COVID-19 deaths per capita be hidden by other, even more important factors, such as the proportion of the population over 60. (I would like to thank Antoine Lévy for providing me with this dataset, which he constructed for the purposes of his analysis in a recent paper, but it goes without saying that none of the opinions I express in this post should be attributed to him.) I also used population-weighted population density rather than population density, because population density is often extremely misleading because even in a very large country, people are usually concentrated in a tiny part of the territory.

As you can see on this graph, even when you restrict yourself to a group of countries that are relatively homogenous in economic, cultural and demographic terms, there is no clear relationship between population density and the number of COVID-19 deaths per capita. You can also see that Serbia, where as I have already noted the second wave has receded without a lockdown, has a population-weighted population density roughly equal to that of France and other countries where pro-lockdown advocates assure us Sweden’s strategy could never work because population density is higher. The same thing could be said about many other places, such as Florida, where the same thing happened. Of course, it doesn’t mean that, other things being equal, population density doesn’t result in higher transmission and in fact I have no doubt that it does, but clearly the effect is not as large as one might have thought, otherwise it would be easier to detect. This example illustrates a recurring phenomenon in debates about the pandemic. People make wild conjectures that often aren’t even supported by the data we have, but assert them as if they were established fact. We’ll see another example of this phenomenon when I briefly discuss what happened in Asian countries that managed to keep the epidemic under control without lockdowns.

Another argument that is often made is that you shouldn’t compare Sweden to countries like France, the UK or Belgium but only to its neighbors, because due to cultural proximity or whatever they provide a better counterfactual of what would have happened in Sweden if the government had decided to lock down. However, as I explained elsewhere, not only is this claim largely gratuitous, but it’s demonstrably false. Indeed, when you infer the number of infections during the first wave from the number of deaths, you find that, by the time its neighbors decided to lock down, the epidemic was already far more advanced in Sweden. Thus, even if Sweden had locked down around the same time as its neighbors and we assume that it would have suddenly cut transmission by a very large factor, which as we have seen is almost certainly false, there would still have been far more COVID-19 deaths in Sweden because a lot more people had already been infected and it would have taken longer for incidence to go down since it was starting from a much higher level. Frankly, it’s incredible that so many people still believe that policy explains most of the difference in outcomes between Sweden and its neighbors. Even if I were wrong about what happened during the first wave, as I already noted, Finland remains almost entirely spared by the pandemic even though restrictions have been even less stringent than in Sweden for months. The same thing could be said about most of Norway. Although nobody knows what they are, there are clearly factors beyond policy that play a major role and explain why Sweden’s neighbors have largely been spared by the pandemic, but people continue to make this comparison as if it proved that Sweden’s failure to lock down explains most of the difference.

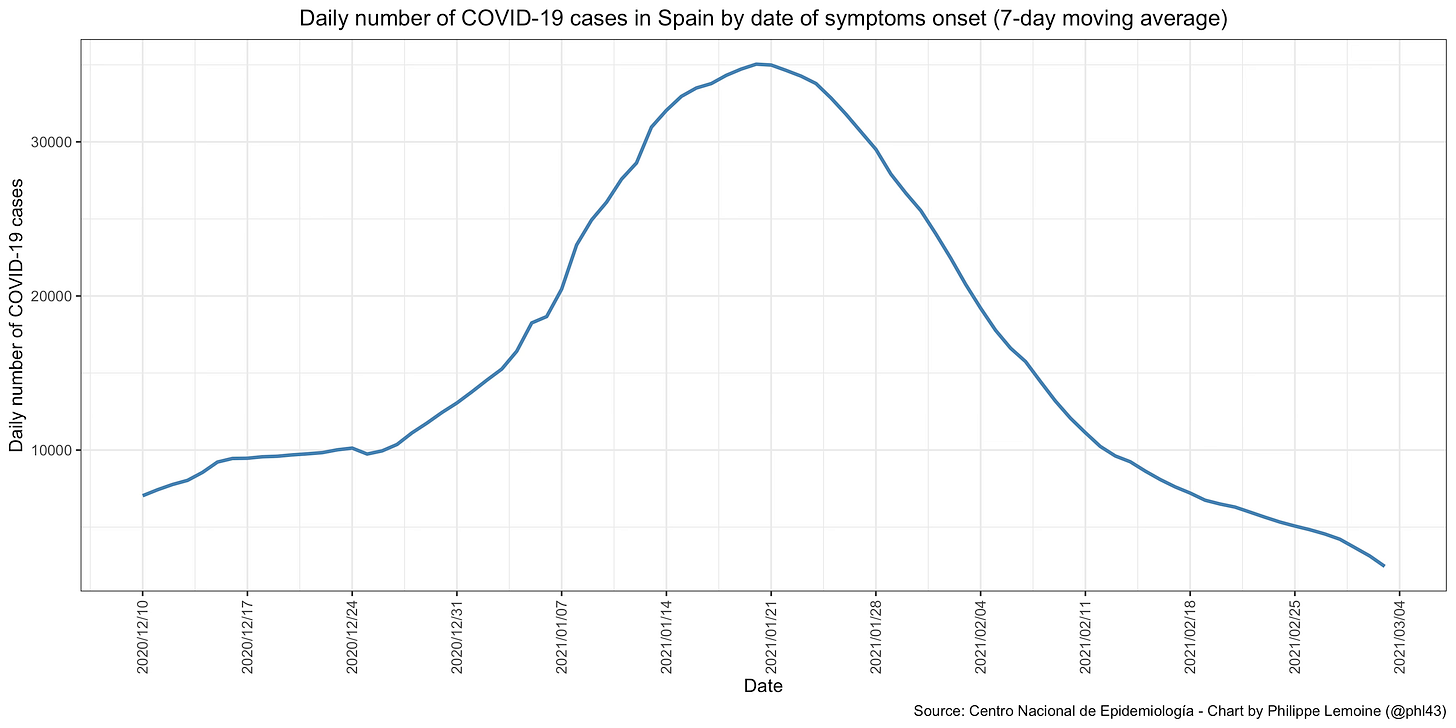

Pro-lockdown advocates like to bring up culture to explain away inconvenient facts, but while I have no doubt that culture affects the course of the epidemic, cultural explanations have repeatedly proved wrong since the beginning of the pandemic, without reducing people’s appetite for them. For instance, when it became clear that the holocaust that pro-lockdown advocates predicted in Sweden had failed to materialize and that COVID-19 mortality was not particularly high over there, many of them started to say that Sweden’s strategy could not be replicated in other countries not just because of population density but also because they lacked the Swedish culture of compliance with government rules. Thus, when incidence started to explode in Spain a few weeks ago and the government refused to lock down (it even prevented local governments from locking down when they tried), they naturally denounced that decision as irresponsible, since what Sweden did could never be replicated in a Latin country such as Spain. Instead, I predicted that incidence would soon begin to fall, which is exactly what happened:

In fact, although I couldn’t have known it when I made that prediction, the number of cases had already started to fall. That’s because data on cases by date of symptoms onset take a while to be compiled, so we only had data on cases by date of report and there is a significant reporting delay.

Now that incidence has collapsed, some of the people who predicted the apocalypse have done a U-turn and now claim there was a de facto lockdown in Spain, on the ground that many regions had put in place stringent restrictions even though they were prevented by the national government from implementing a complete lockdown. But it’s still the case that almost everywhere in Spain restrictions were less stringent than in the UK or even France, which is not even locked down but where there is a curfew at 6pm and bars and restaurant are closed except for take-out. Moreover, in some regions (such as Madrid), restrictions remained very limited. Bars and restaurants were allowed to remain open at all time until January 18, 2021 when they were forced to close at 10pm, while a curfew starting at 11pm came into effect. On January 25, the closing time for bars and restaurants was changed to 9pm, while the curfew was advanced to 10pm. In other regions, restrictions were more stringent, sometimes a lot more, but again they remained less stringent than in France or the UK almost everywhere. Thus, I don’t see how anyone can seriously claim that Spain was de facto on lockdown when incidence started to fall, if by that we mean something like what the country did last Spring or what the UK or even France are currently doing. If pro-lockdown advocates in France or the UK really think that, then they should ask that bars and restaurants be reopened over there, but somehow I don’t think that’s going to happen.

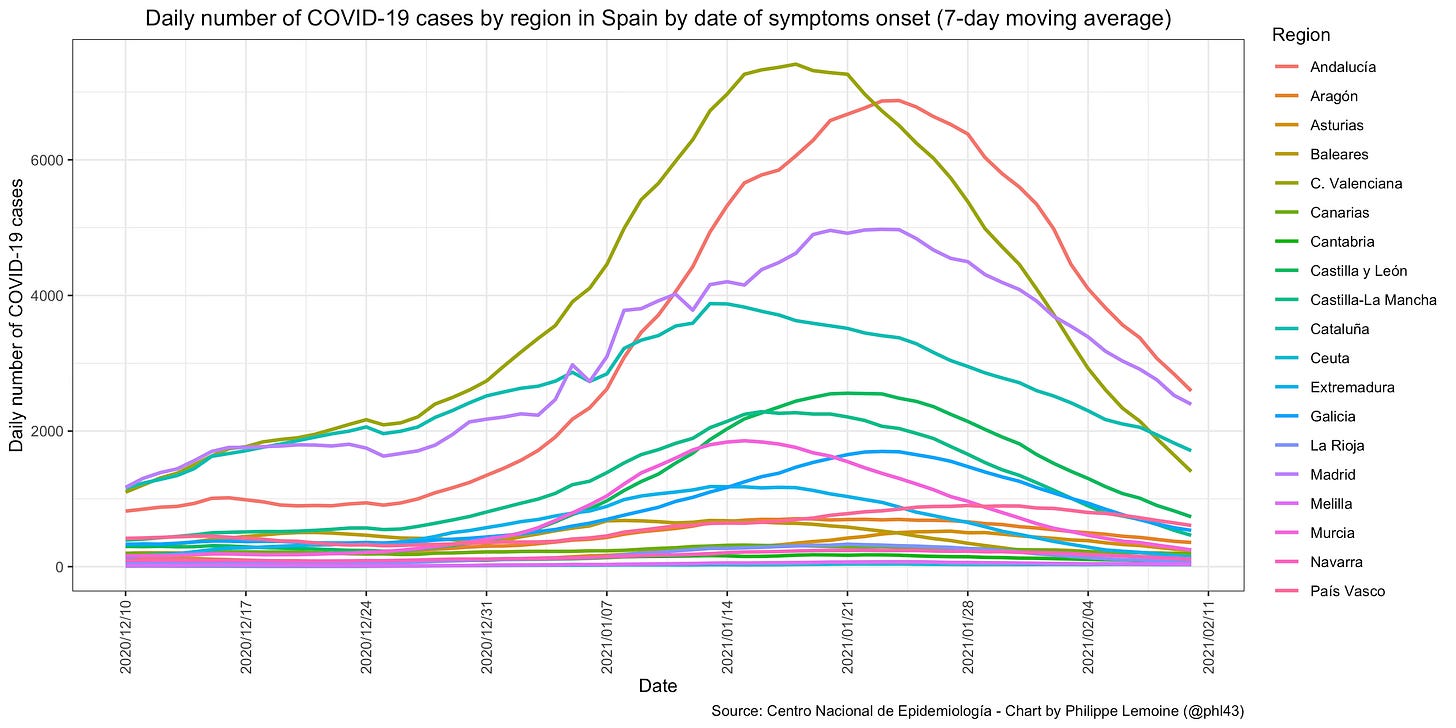

Despite the fact that restrictions in Spain ranged from very limited as in Madrid to very stringent as in Murcia, incidence started to fall everywhere around the same time in January:

You may be able to argue that it started to fall a bit earlier and that it has been falling a bit faster in regions with the most stringent restrictions in place, which doesn’t mean that it was because of that, but it still fell everywhere including in regions where restrictions were very limited. In fact, if you look at the timing of the fall and compare it to that of the restrictions in each region, you will generally find that incidence started to fall before the most stringent restrictions came into effect, especially when you take into account the period of incubation. So the prediction that Sweden’s strategy wouldn’t work in Spain because it doesn’t have the right culture proved spectacularly wrong.

I’m sure there are plenty of differences between the places that have locked down and those that have not, and even that some of them affect the epidemic, although the truth is that nobody knows what they are or how exactly they do so. But places that have not locked down or put in place very stringent restrictions are so diverse economically, culturally, demographically, etc. that if incidence nevertheless started to fall long before the herd immunity threshold was reached in all of them, it’s extremely unlikely that it’s because they all happen to have characteristics that make not locking down a viable option, whereas everywhere else this policy would lead to the disaster predicted by pro-lockdown advocates as incidence would continue to increase quasi-exponentially until the herd immunity threshold is reached. At this point we have so many examples, and no counter-examples, that such a claim is akin to magical thinking. It’s far more likely that, whenever and wherever incidence starts increasing quasi-exponentially somewhere, the same mechanisms push below 1 long before the herd immunity threshold is reached even when there is no lockdown or stringent restrictions. In the next section, I propose a theory of what this mechanism could be, which also explains why it often looks as though lockdowns and other stringent restrictions are very effective and why many governments have used them despite their cost and limited effectiveness.

A theory of why lockdowns and other stringent restrictions don’t make a huge difference

Many people assume that, without a lockdown, when incidence starts increasing quasi-exponentially, it will continue to rise in that way until the herd immunity threshold is reached. But as we have seen, this is not what happens and therefore it doesn’t make sense to extrapolate from current growth by assuming it will continue until something like 66% of the population has been infected. It’s true that, in a standard compartmental model, incidence rises quasi-exponentially until the attack rate approaches the herd immunity threshold, but that’s only the case when, among other things, the contact rate is assumed to be constant. However, with or without lockdown, the contact rate never remains constant because people respond to epidemic conditions by changing their behavior, which affects the contact rate and therefore also R. (I will pass over the fact that, beyond the assumption that both the contact rate and the generation interval remain constant, which can easily be relaxed, the model from which the formula that everyone is using to compute the herd immunity threshold is totally unrealistic, in particular because it assumes a perfectly homogenous population, so that we don’t actually know what the herd immunity threshold really is.) Beside, even if this were not the case, given that R has been hovering between 1 and 1.5 for months almost everywhere, we’d still expect the epidemic to start receding long before 66% of the population has been reached anyway.

To the extent that restrictions have any effect on transmission, they presumably have both direct and indirect effects. Direct effects consist in physically preventing certain events that contribute to the spread of the virus. For example, if the government bans large gatherings and the ban is respected, it becomes physically impossible for a single person to infect hundreds of people at the same time. But presumably restrictions also have indirect effects because they send a signal to the population, which can translate into behavioral changes that in turn can affect the contact rate and/or the generation interval. (The contact rate is a quantity used to model how often people meet each other in a way that results in someone getting infected, while the generation interval is the time between the moment someone is infected and the moment they infect someone else.) My theory about the epidemic is that, once you have some basic restrictions in place, such as a ban on large gatherings, then unless perhaps you go very far as the Chinese authorities did in Wuhan (which I think is neither possible nor desirable in a democracy), more stringent restrictions have a rapidly decreasing marginal return because they are a very blunt instrument that has a hard time targeting the behaviors that contribute the most to transmission and people reduce those behaviors on their own in response to changes in epidemic conditions such as rising hospitalizations and deaths. However, as I explain below, it doesn’t mean that their marginal cost also decreases rapidly. For instance, a 6pm curfew as in France probably doesn’t have much impact if any on transmission, but it arguably has a large effect on people’s well-being.

In simple terms, what this means is that, once the authorities have put in place relatively limited restrictions, everything they do after that has an increasingly small effect on transmission and consequently the most stringent restrictions only have a relatively negligible impact on the dynamics of the epidemic. (Again, it’s plausible that it ceases to be true if you go very far as the Chinese authorities did in Wuhan, but even in China we don’t really know for sure that lockdowns were essential to the country’s ability to suppress the virus. Indeed, neighboring countries were able to do the same thing without lockdowns, so I don’t see why people are so confident that lockdowns are what did the work in China as opposed to whatever did the work in other East Asian countries.) If this were not the case, given how much variation in policy there is between regions, the graphs of the cumulative number of COVID-19 deaths in US states or European countries I have shown above would almost certainly look very different. On the other hand, there is very little variation in more limited non-pharmaceutical interventions such as bans on large gatherings, which are in place almost everywhere, so this doesn’t tell us they only have a small effect and I think we have good reasons to think they have a significant one even though ultimately even that is not clear. Again, I’m not claiming that lockdowns and other stringent restrictions have no effect on transmission, I’m just saying that when you look at the data it’s hard to convince yourself they have more than a relatively small effect and it’s impossible to maintain that it’s as large as pro-lockdown advocates claim.

Moreover, when I say that people’s voluntary behavior changes in response to changes in epidemic conditions, I’m not saying that the mechanism is necessarily just the aggregate reduction in social activity. For instance, since presumably not everybody respond in the same way to changes in epidemic conditions, it’s possible that a rise in incidence, which eventually results in a rise of hospitalizations and deaths that scare people into modifying their behavior, temporarily creates more heterogeneity in the population because some people will react more strongly to this change in epidemic conditions than others, which in turn lowers the herd immunity threshold until incidence goes down and eventually people go back to their previous behavior. One could also imagine that behavior changes increase the generation interval, which even keeping R constant would lower the growth rate of the epidemic. Moreover, it’s likely that the type of social activity people engage in and not just how much of it they engage in matters a lot. If people disproportionately reduce the types of social activity that contribute the most to transmission, a relatively small reduction in aggregate social activity could result in a significant reduction in transmission.

In short, I make no hypothesis on the specific mechanisms underlying the feedback mechanism my theory posits at the micro-level, because I don’t think we really understand what’s going on at that level. I just claim that people’s behavior changes in response to changes in epidemic conditions and that whatever the specific mechanisms at the micro-level those behavior changes eventually make the epidemic recede even when a relatively small share of the population has been infected. Of course, I’m not claiming that the feedback mechanism posited by my theory is the only factor driving the dynamics of the epidemics, but I think it’s probably the main factor explaining why over and over again R dropped below 1 in places where the prevalence of immunity just wasn’t high enough to explain that, as shown by the fact that eventually the epidemic blew up again. (There are other possible explanations and most of them aren’t even mutually exclusive with my theory, but for various reasons I won’t get into, I don’t think they can really explain the data.) However, at this point, I think the prevalence of immunity is high enough in many places that it can plausibly explain why incidence is falling even in the absence of any behavior changes. But I doubt that incidence wouldn’t start rising again if everyone returned to their pre-pandemic behavior.

My theory predicts that, in places where the IFR and the hospitalization rate are lower because the population is younger, the virus will be able to spread faster and the attack rate (i. e. the proportion of people who have been infected) will be higher. Indeed, if the feedback mechanism I postulate operates through exposure to information about the number of deaths and hospitalizations, people won’t start changing their behavior enough to push R below 1 until the daily numbers of deaths and hospitalizations scare them. In a place where people are very young, incidence will have to rise much higher than in developed countries, where a large share of the population is over 60, before this happens. For example, pro-lockdown advocates often cite the case of Manaus, a Brazilian city where a study concluded that about 75% of the population had already been infected by October, which didn’t prevent another wave at the beginning of the year. First, I think it’s extremely implausible that 75% of the population had really been infected at the time, since the study is based on a non-random sample and that estimate was obtained after significant corrections to account for antibody waning, while seropositivity never exceeded 44% in any sample. (I also think it’s a bad idea to generalize from what seems like a clear outlier, but let’s put that aside.) In any case, it’s clear that the attack rate in Manaus is much higher than anywhere in the US or Europe, but this is not surprising if my theory is true.

Indeed, the population in Brazil is much younger than in the US or Europe, so although the attack rate climbed much faster over there, the numbers of deaths and hospitalizations have not. According to official statistics, as of December 8, 2020, 3,167 deaths had been attributed to COVID-19 for a population of approximately 2.2 million, which corresponds to a rate of about 1,438 deaths per million. By comparison, at this point, 11,593 deaths had been attributed to COVID-19 in Madrid. Since that city has a population of about 3.3 million, this corresponds to a death rate of approximately 3,470 per million. Thus, by December 8, the number of COVID-19 deaths per capita was actually higher in Madrid than in Manaus and presumably the same thing was true of the number of hospitalizations. However, even if you don’t buy that 75% of the population had already been infected by October in Manaus, the attack rate was no doubt much higher than in Madrid where seroprevalence was only ~11% in May and the vast majority of deaths were recorded before that. But if my theory is true, there is nothing surprising about that, since it’s only to be expected that it would take longer for people to change their behavior in a place where it takes longer for hospitalizations and deaths to start piling up because the population is younger. Thus, not only are such cases not counter-examples to my theory, but they’re actually predicted by it. I fully expect that, by the time the pandemic is over, we’ll find that the attack rate is higher in places with a younger population even controlling for various relevant variables.

Of course, as I have formulated it, this theory is very vague. In particular, I don’t give any precise figure to clarify what I mean by “rapidly diminishing marginal return” or “not very large effect”, but the truth is that I don’t think you can say anything more precise and people who claim otherwise are trying to fool you or are fooling themselves. I constantly see people on both sides of the debate throwing studies at each other that purport to estimate the effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions and allegedly prove that lockdowns and other stringent restrictions either work or don’t work. Those studies give very precise estimates of the effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions with confidence intervals that look very “scientific”, but all of that is completely meaningless because the models are poorly specified, the studies are plagued by omitted variable bias, measurement error, simultaneity, etc. Just remember how intractable it was to even figure out exactly when incidence started to fall in England, where there are much better data than virtually anywhere else in the world, then just imagine trying to disentangle causality in that mess with far noisier data. No wonder that you can find such inconsistent results in the literature on the effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions. In my opinion, the only studies that you may be able to take kind of seriously are those that use a quasi-natural experiment to estimate the effect of restrictions in a single country, such as this study on locally imposed lockdown in some Danish municipalities last November, which found no clear effect. But the conclusions of such studies can’t easily be generalized to other countries, so even they are not that useful.

However, I know that studies published in prestigious scientific journals exert a strong pull on people, so let me say more about the literature on the effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions. There are so many studies that claim to show that restrictions have a very strong effect on transmission, and so few people who have actually looked at them in detail, that I know people won’t take seriously my theory unless I do. In fact, when you take a close look at those studies, it becomes clear that none of them can possibly refute my theory and that all of them are completely unreliable if my theory is true. Most studies about the effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions fall roughly into 2 categories. First, you have studies that fit an epidemiological model, typically a compartmental model of some kind, on epidemic data. Non-pharmaceutical interventions are assumed by the model to affect transmission in a certain way and their effect is estimated by fitting the model. The other type of studies use econometric or machine-learning methods to estimate the association between non-pharmaceutical interventions and the growth rate of the epidemic or some related quantity such as R.

The most famous example of the first type of study is probably Flaxman et al.’s paper that was published in Nature last June and has already been cited almost 750 times. This paper concluded that non-pharmaceutical interventions and lockdowns in particular had saved more than 3 million lives in Europe alone during the first wave and is still cited all the time by pro-lockdown advocates. I have already written a very detailed take-down of that study, which I strongly encourage you to read, so I’m not going to go over it again. To show how ridiculous the paper is, it suffices to say that, in order to obtain that estimate, the authors used a counterfactual in which more than 95% of the population had been infected by May 4 in every country they included in the study. Of course, even 9 months later, there is not a single country in the world as far as we know and certainly no country in Europe where the attack rate is even close to that. This is one of several little details the authors of that study decided not to state in the paper. The fact that such a preposterous estimate is still being taken seriously by so many people, including professional epidemiologists, tell you everything you need to know about how broken the scientific literature on the effect of non-pharmaceutical interventions is.

As I explain in my post about this study, their own results actually support my theory that, once a few very limited restrictions are in place, voluntary behavioral changes are enough to push R below 1 long before the herd immunity threshold is reached. Indeed, they found that non-pharmaceutical interventions in Sweden, where there was no lockdown and restrictions were very liberal, had reduced transmission almost as much as in the rest of Europe. Nevertheless, they concluded that only lockdowns had a meaningful effect on transmission, because they included a country-specific effect in the model that allowed the effect of the last intervention to vary in each country. In every country besides Sweden, the last intervention was a lockdown and the country-specific effect is never very large, but in Sweden the last intervention was a ban on public events and the country-specific effect was gigantic. As I noted in my reply to Andrew Gelman’s comment about my post, the result was that while their model found that banning public events only reduced transmission by ~1.6% everywhere else, it found that it had reduced it by ~72.2% in Sweden, almost 45 times more. Of course, this never happened, there is just no way unless you believe Sweden is full of anti-covid magical fairies that banning public events was 45 times more effective in Sweden than anywhere else.

The fundamental problem with this paper is the same as with basically every other paper in that category I distinguished above and it’s that it assumes that only non-pharmaceutical interventions affect transmission. Thus, despite what people like the folks behind The Covid-19 FAQ continue to claim (even though I already explained to them why it was demonstrably false), there is no way studies of that sort could ever show that voluntary behavior changes wouldn’t push R below 1 long before the herd immunity threshold is reached even in the absence of a lockdown, because they literally rely on models that implicit assume that voluntary behavior changes have no effect whatsoever on transmission. This is not just true of Flaxman et al.’s paper, but also of several other highly-cited studies, such as Brauner et al.’s paper in Science or more recently Knock et al.’s paper about the epidemic in England. Basically, what they do is assume that R or a related quantity such as the contact rate is affected by non-pharmaceutical interventions in a certain way, then fit the resulting model to the data to estimate the effect each of those interventions has. At best, what this kind of study can do is answer the question: if we assume that only non-pharmaceutical interventions affect transmission, and make a bunch of other largely arbitrary assumptions, what effect did each non-pharmaceutical intervention had on transmission? But we know that non-pharmaceutical interventions are not the only thing affecting transmission, so papers that follow this approach have no practical relevance whatsoever and predictions based on them are completely meaningless.

A second type of study doesn’t use an epidemiological model but tries to establish correlations between non-pharmaceutical interventions and the growth rate of the epidemic or some related quantity such as with traditional econometric or sometimes machine-learning methods. Basically, what they do is look at the epidemic in a bunch of different countries/regions and try to find if non-pharmaceutical interventions are associated with a reduction in the rate at which it grows, which is the case if the epidemic tends to grow less when non-pharmaceutical interventions are in place. The fundamental problem with this approach is that, if I’m right that people respond to epidemic conditions by modifying their behavior when hospitalizations and deaths start blowing up, then the epidemic’s growth rate will tend to start falling when the authorities decide to implement non-pharmaceutical interventions, because the people in charge also tend to do that when hospitalizations and deaths increase. So this kind of study would probably find a correlation between non-pharmaceutical interventions and a reduction of the epidemic’s growth rate even if the former didn’t have any effect on transmission, because the changes in epidemic conditions that make the authorities inclined to implement non-pharmaceutical interventions also make people change their behavior in ways that reduce transmission.

Similarly, it’s likely that if I gave you a pill that only contains sugar but told you that it’s a medicine that makes fever go down and you were the sort of person that only takes medicine when they’re at the point of death, you’d find that your temperature generally starts going down soon after you take it. But it would be wrong to conclude that it’s because the pill made your temperature go down. Indeed, we know the pill doesn’t do anything, it’s just sugar after all. The reason you’d probably find that your temperature usually goes down soon after you take the pill is that, since you’re the kind of person that only takes pill when they have already been in agony for days, by the time you finally take it, your immune system is mostly done fighting whatever caused the fever in the first place and your temperature was about to start falling anyway. This is what people call endogeneity when they want to sound intelligent, but as you can see, the basic idea is simple enough and anyone can understand it. I think it’s basically what happens with studies that look for correlations between non-pharmaceutical interventions and the epidemic’s growth rate. Again, I’m not saying that non-pharmaceutical interventions have no effect whatsoever, but they typically start around the time people start voluntarily changing their behavior, which hopefully I have convinced you probably has a very large effect on transmission. To be clear, it’s hardly the only problem with those studies, which among other things have to deal with massive measurement error and absolutely terrible data, but that alone makes the whole enterprise hopeless in my opinion.

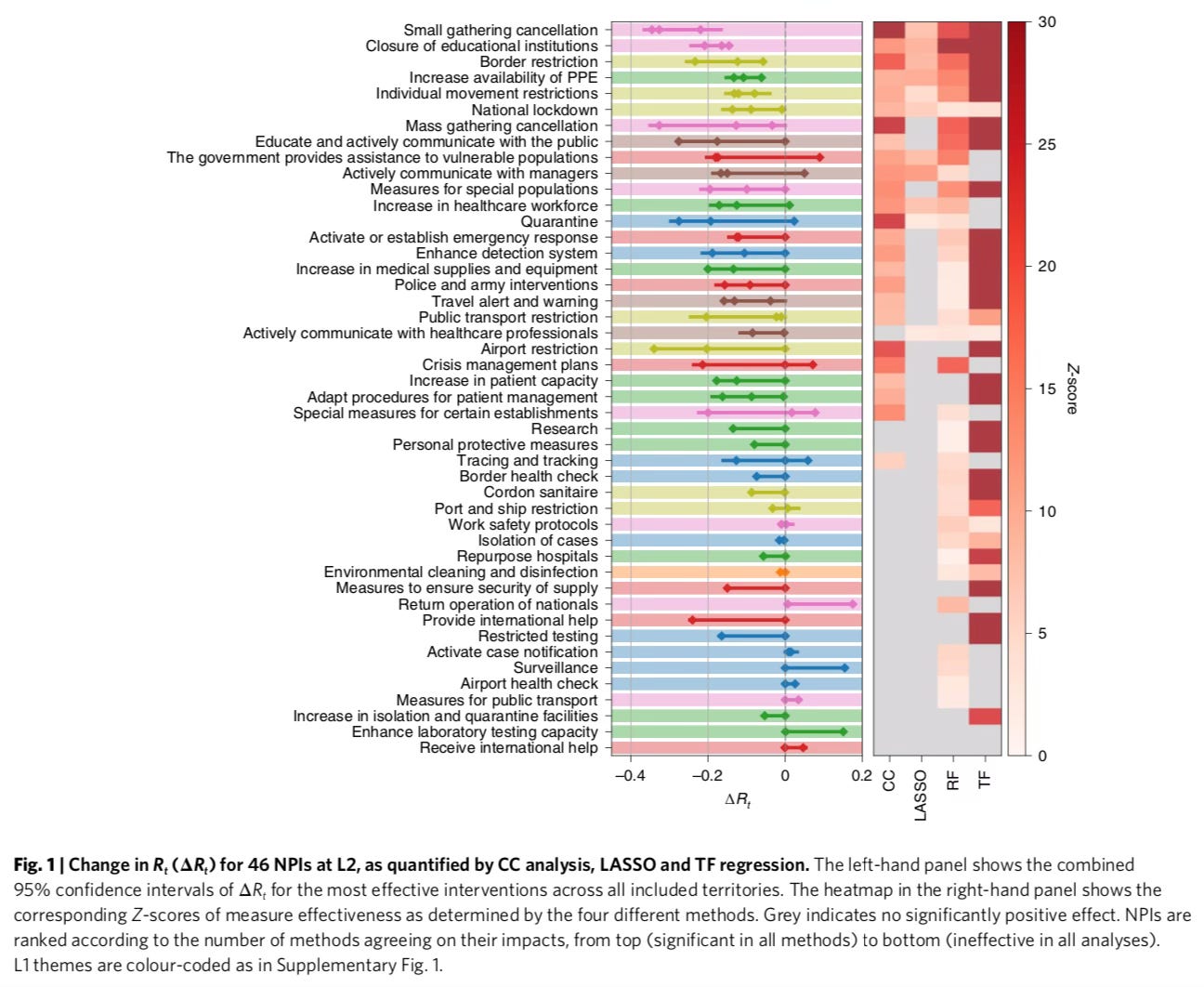

A good example of this type of study is the paper by Haug et al. that was published in Nature back in November, which is one of the most sophisticated in the second category of studies. The authors used several different statistical approaches to estimate the relationship between non-pharmaceutical interventions and R. Here is the figure that summarizes what they found:

As you can see, if this study is to be believed, while some interventions are not effective, several of them have a large effect on transmission. Many people see that and conclude that it has been scientifically proven that restrictions had a very large effect on transmission, but as I already explained, this kind of study can’t establish causality and we have very good reasons to think their results are extremely misleading. What this means is that, if you use them to predict what is going to happen depending on what policy you implement, you will almost certainly get things catastrophically wrong. But it never occurs to people to check whether studies of that sort perform well out-of-sample, and reviewers apparently don’t ask their authors to do it, so they happily go around making policy recommendations based on papers that have essentially no practical relevance.

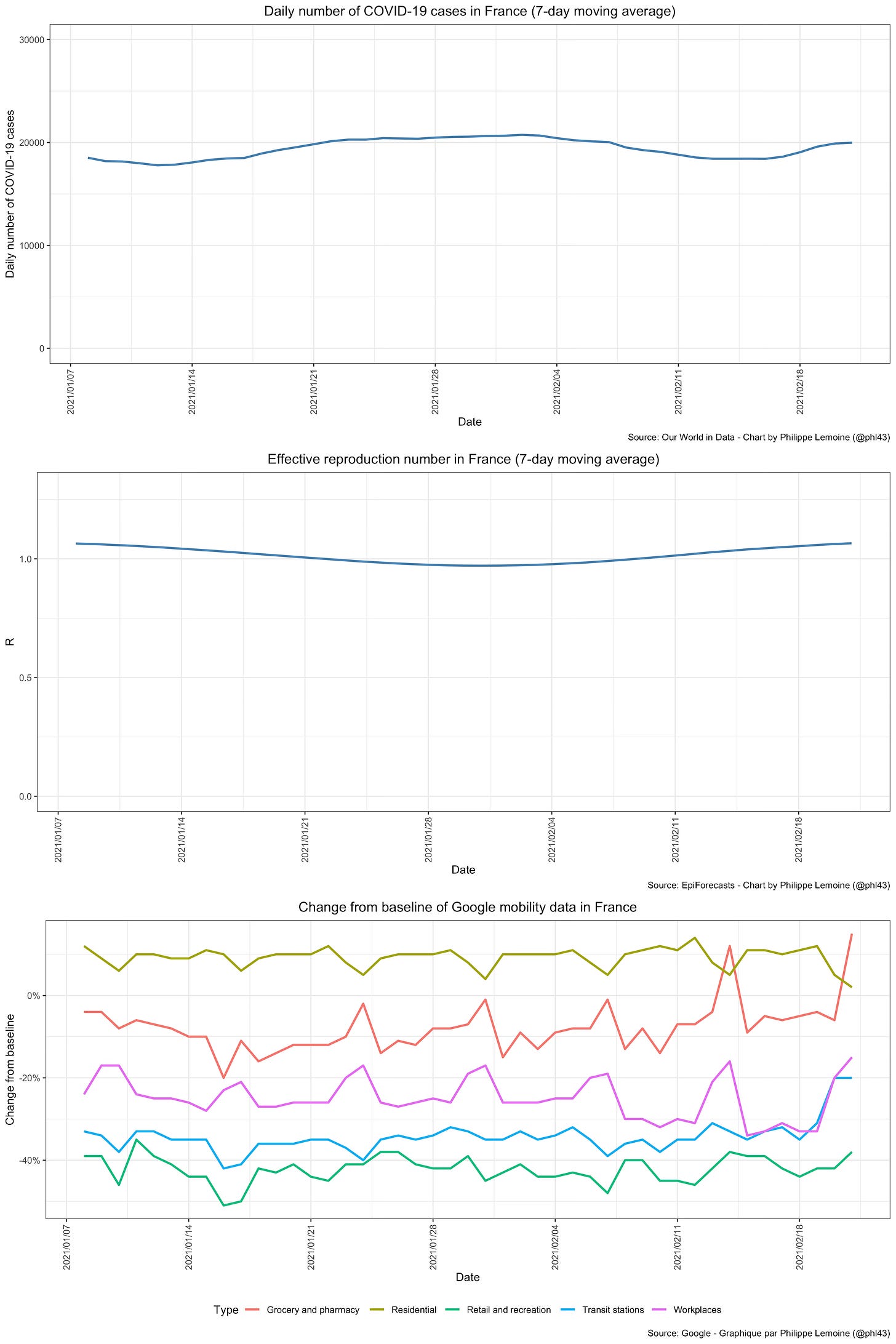

In the case of the Haug et al.’s paper, despite the fact that again it’s pretty sophisticated by the standards of that literature, you just have to eyeball a graph of R in various US states during the past few months for 5 seconds to see that it performs horribly out-of-sample:

I didn’t even bother to do this rigorously, but if you look up the restrictions in place in those states during that period and check Haug et al.’s paper, it’s obvious that we should have seen widely different trajectories of R in those states and in particular that it should have been consistently much higher in states like Florida that remained almost completely open than in those like California that have put in place very stringent restrictions, but as you can see that’s not what happened. I only show a handful of states because otherwise the graph would be illegible, but I didn’t cherry-pick and, if you plot R in every state, you’ll see that it follows a very similar trajectory everywhere. You can do the same thing for Europe and you will reach the same conclusion.

Only a handful of studies make a serious attempt to address the endogeneity problem I have identified above. The best is probably the paper by Chernozhukov et al. about what happened in the US during the first wave that was recently published in the Journal of Econometrics, which as far as I know is the most sophisticated attempt to estimate the effects of lockdown policies in the literature. Indeed, unlike most papers in the literature about the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions, it uses statistical methods that can in principle establish causality. The authors modeled the complex ways in which policy, behavior and the epidemic presumably interact. In particular, their model takes into account the fact that people voluntarily change their behavior in response to changes in epidemic conditions and that it’s typically around the same time that the authorities decide to implement non-pharmaceutical interventions, because they react to the same changes in epidemic conditions as the population, so if you’re not careful it’s easy to ascribe to non-pharmaceutical interventions what is really the effect of people’s voluntary behavior changes that would have occurred even in the absence of any government interventions. Again, it’s much better than most other studies I have read on the issue and the authors should be commended for at least trying to address the methodological problems I pointed out above, but I still don’t think you should buy their conclusions.

The effect sizes advertised in the abstract are pretty large but very imprecisely estimated and the rest of the paper shows that most of them are not robust to reasonable changes in the specification of the model. Their more robust finding is that mandating face masks for public-facing employees reduced the weekly growth in cases and deaths by more than 10%, which remains true in almost every specification of the model they tried, though not in all of them. Based on one of the specifications that was associated with the largest effect, they simulate a counterfactual in which face masks were nationally mandated for public-facing employees on March 14 and find that it would have reduced the cumulative number of COVID-19 deaths in the US by 34% during the first wave, but with a 90% confidence interval of 19%-47%. They are unable to estimate the effect of closing K-12 schools, but conclude that stay-at-home orders and the closure of non-essential businesses also reduced the number of cases and deaths, even though the effect is not significant in most of the specifications they tried. Even with the specification they used to define their counterfactual, they find that if no state had ordered the closure of non-essential businesses, the number of deaths would have been 40% higher by the end of May, but the 90% confidence is interval is extremely wide at 1%-97%. According to that same counterfactual, had no state issued a stay-at-home order, the number of deaths would have been somewhere between 7% lower and 50% higher.