One of the surprises of the 2020 election was the increase in Trump vote share among minorities. In fact, Figure 1 shows that there has been a rising trend in the exit polls since 2012 in favor of Republicans. For the black vote, the rise has been continuous since Obama’s second term began in 2008. In that year, just 4 percent of African-Americans voted for John McCain. This year, 12 percent of blacks voted for Trump. What explains the rise? Will it continue?

For Musa al-Gharbi, this represents a rebound following Obama’s historic achievement of becoming the first minority president. Yet other, slower-moving dynamics are also afoot, which would suggest there is something longer term at work.

Regarding core demographics, the first keys to understanding variation in African-American voting are age and gender. To examine this question, CSPI commissioned two surveys from Qualtrics of African-American respondents, one in April-May 2020, well before the election, and another from November 3 to December 1, 2020, largely after.

The total number of black respondents across both studies was 1,730, making this one of the largest recent surveys of African-Americans. The participants were recruited to achieve a nationally representative sample of people by age, gender, region and education.

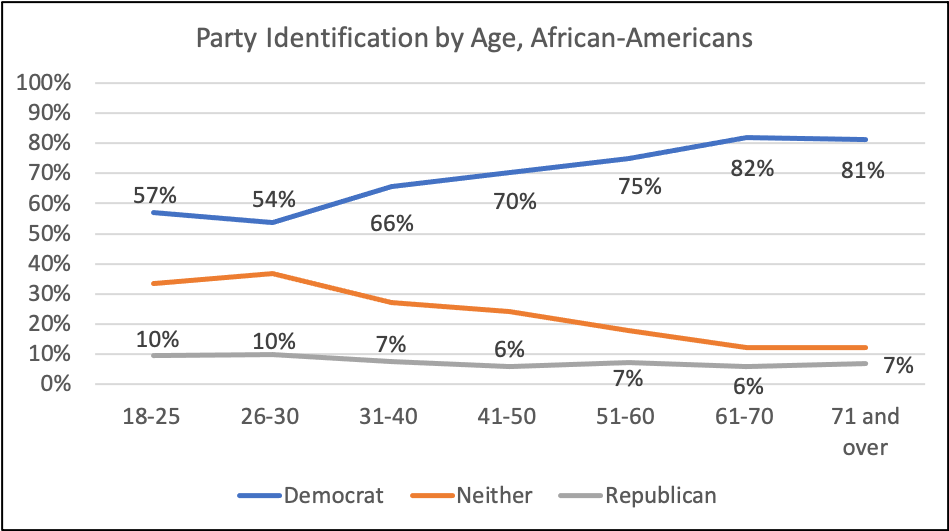

In Figure 2, we can see that identification with the Democratic Party tends to rise with age, from 54-57 percent among those under 30 to 81-82 percent among those over 60. Importantly, the Democrat to Republican ratio of identifiers is just 5.5:1 among those under 30, but reaches 13:1 among blacks over 60.

Comparing with whites in the April-May survey, and controlling for gender, marital status, region and education, shows that this age pattern is unique to the black community, and independent of the main demographic factors. Figure 3 shows that just 19 points separate young blacks and whites in Democratic identification, but that gap jumps to 42 points among those over 30.

Age and the 2020 Black Vote

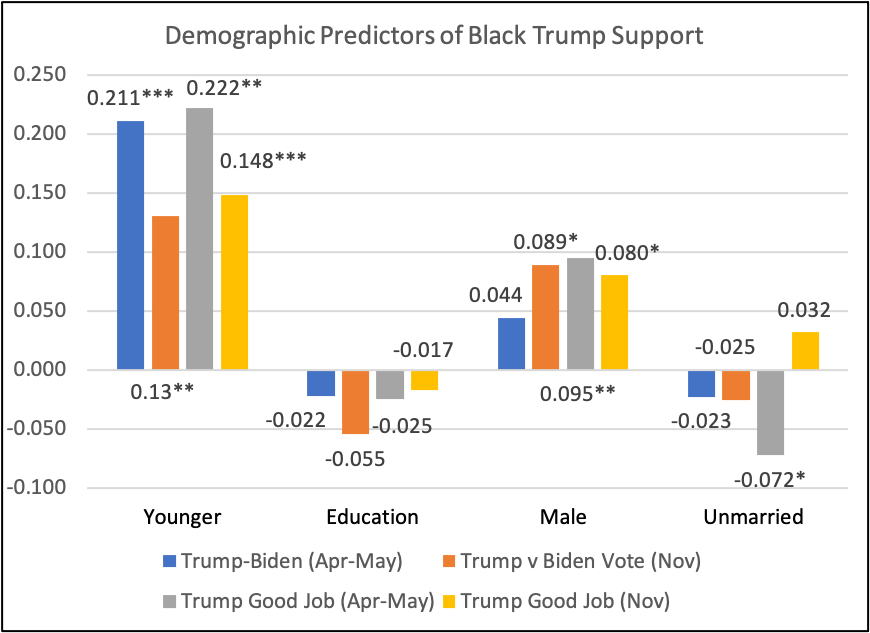

When it comes to predicting which blacks voted for Trump in 2020, the most important demographic factor is age. In the April-May survey, we asked people to rank their likelihood of voting for one of the main party candidates on a 5-point scale from ‘sure to vote Biden’ to ‘sure to vote Trump.’ In the November survey we asked how people voted, excluding those who didn’t vote for one of the two main parties. We also asked, in both surveys, whether they agreed or disagreed with the statement ‘President Trump is doing a good job as president.' The results of these questions, in the order just mentioned, are shown in Figure 4.

We clearly see that age is the most consistent predictor of black Trump support, with younger African-Americans more likely to vote for Trump in relation to Biden, and more likely to say he is doing a good job. The voting effect arises because younger African-Americans are less likely to vote, and more likely to vote for third parties, than older African-Americans. Since blacks lean so heavily to Biden, this withdrawal hurts Biden more than Trump among the youth. Just comparing the two-party vote, young voters are not more likely to vote Trump instead of Biden than older voters.

In keeping with Figure 3 above, younger whites were not significantly more likely to endorse Trump or to vote for him than older whites. Thus the age dynamics we observe around youth nonvoting and independence are distinctive to blacks and not a general trend.

Much, but not all, of the age effect among blacks runs through party identification: when that variable and ideology are held constant, age is no longer a statistically significant predictor of the Trump-Biden balance. In addition, being younger continues to significantly predict black support for whether Trump is doing a good job.

Including non-voters and third-party voters, among blacks 35 and under, 60% voted for Biden and 8% for Trump, compared to 86% for Biden and 9% for Trump among those over 60. The black youth do not appear to be particularly enamored with Trump or the Republican Party as much as they appear to be less enthusiastic about Democrats, relative to their elders.

Black men are significantly more likely than black women to say Trump is doing a good job as president, and, when focusing only on the two-party vote, are more likely to say they would vote for him (April-May) or voted for him (in November). However, among black men who strongly agreed with the statement, ‘I consider myself completely heterosexual, not lesbian, gay, bisexual or transsexual’ (53 and 65 percent of samples), there was no significant association with Trump support or voting. This contradicts the theory that black male machismo may have played a role in any black shift towards Trump.

Black Identification

One of the most important attitudes that correlates with party identification among black Americans is their attachment to being black. When asked, ‘How important is being black to your identity?’ in the two surveys, 49 and 61 percent say ‘extremely important’ and another 25 and 23 percent say ‘very important’. This leaves just 16-26 percent with a weaker black identity. Black men and conservatives are, in one of two surveys, more likely to have weaker black identities than women and liberals, but this is not true for younger African-Americans.

What comes out extremely powerfully, however, is the link between weaker black identification and weaker Democratic support. Figure 5 shows that only a minority of African-Americans with weaker black identity (40-52 percent) identify with the Democrats. This compares to higher numbers among those for whom black identity is ‘very’ (67 percent Democrat) or ‘extremely’ (76 percent Democrat) important.

Furthermore, even when controlling for party identification and ideology, black identity is significant in three of four of the models based on the data in Figure 4, and close to significance in the fourth. In short, black identification is very important for black Democratic identification. Anything that weakens black identification is likely to affect black Democratic support.

These results are consistent with the work of Tasha Philpot, who writes that higher group consciousness is associated with Democratic affiliation among blacks, and that younger African-Americans are more Republican than their elders.1 Blacks who attend majority-black churches are significantly more likely to have a strong black consciousness. Churches also help organize the vote, reinforcing Democratic identification. In the April-May survey, black Protestants were significantly more attached to being black than blacks of other religious backgrounds, and in both surveys, those of no religion had weaker racial identity than Christians.

Black Democratic attachment is a community norm, Philpot writes, and is less strongly mediated by ideology than it is for whites. The shift of African-Americans out of historically black communities, and their rising rate of interracial marriage, heralds a possible diminishing of black consciousness.2 The move away from the embrace of structures of neighborhood, church and ethnic community weakens social pressure to identify as and vote Democrat.

The Importance of Black Neighborhoods

Figure 6 shows that, after controlling for age, gender, education and religion, the likelihood of an African-American saying their black identity is ‘extremely important’ to them rises from 55 percent to 71 percent as we move from a neighbourhood with almost no African-Americans to one that is 90 percent African-American. In fact, black share in ZIP code is still significantly associated with higher black identity after controlling for ideology and party identification.

It is difficult to say which way the causal arrow points, as blacks with a strong racial identity may simply decide to live around people more like themselves. Nonetheless, black-white segregation has been declining, leading to an outflow of African-Americans from heavily-black neighborhoods.3 This, along with interracial marriage and secularization, likely attenuates connections to black identity and, by extension, Democratic party identification. This process is likely to continue, potentially contributing further to an erosion of the Democrats’ overwhelming share of the African-American vote.

Philpot, Tasha S. 2017. Conservative but Not Republican. Cambridge University Press, pp. 87-88, 149.

Pew Research Center. May 18, 2017. Available at https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2017/05/18/1-trends-and-patterns-in-intermarriage/.

Urban Institute. 2020. "Residential Segregation Is Declining. How Can We Continue to Increase Inclusion?" Available at https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/residential-segregation-declining-how-can-we-continue-increase-inclusion.