The Coming Ukrainian Counteroffensive

Why Russian offense is finished, growing Ukrainian strength, and what to expect in the next few months

Senator Angus King recently called Ukraine’s preparation for its impending counteroffensive “the longest windup for a punch in the history of the world.” Why has the windup been so long? The answer is pretty simple: Ukraine is waiting for the mud to dry.

The new brigades are trained and ready to go — reports vary, but there are maybe a dozen or so, plus replacements to replenish existing units. Anywhere from 40-60,000 fresh troops trained in combined arms maneuvers are ready to join the fight. They largely have old equipment; Ukraine has given its new Western armor to its most experienced units, intending them to spearhead the assault. At the same time, Ukraine’s spring muddy season has lasted unusually long this year. But the weather has gradually warmed over the last month, the rains are becoming less frequent in Luhansk, Ukraine is launching probing counterattacks along the front line, its strikes on Russian supply lines are picking up, and the ground is beginning to dry.

But maybe not: as I write, the weather forecast now predicts significant rain in the week ahead, especially in the Zaporizhzhia region, possibly muddying things up again until mid-June. We’ll see. The mud is basically the one thing Ukraine is waiting on at this point. The Ukrainians won’t launch suicidal assaults plowing their tanks into deep mud just because internet observers are itching to see action.

Since Ukraine is likely to make a major move within the next month or so, this is an opportune time to assess what to expect in the near future, explain why I think Russia is finished as an offensive force, and lay out Ukrainian strategic options.

The Stakes

Throughout this war, we’ve seen a number of illustrations of Clausewitz’s maxim that war is the continuation of politics by other means. Ukraine’s looming counteroffensive has two major goals: first, reclaim territory from Russia, and second, be seen to do so in order to sustain Western support.

This has clearly become a proxy war between Russia and NATO, supercharging the political considerations inherent to any war. Ukraine’s goal is to wheedle as much military aid as humanly possibly out of NATO, especially the United States. The United States’ goal is more complex: give enough aid to push Russia back, but not so much that its proxy war with Russia escalates into an actual one.

This dynamic has created a Hunger Games scenario where Ukraine is constantly playing to the cameras to cajole extra gifts from the wealthy sponsors who watch its every move over the internet in real time. I had decided against using this analogy until I saw Ukrainians themselves using it. There is something grotesque and sobering about finding yourself in this position, and writing about it. But it is what it is.

A certain strain of America First politician views every bit of aid to Ukraine as something that could’ve been spent on their preferred hot-button issue instead. They can be identified by pleasing soundbites like “Why are we worried about an invasion on the other side of the world when our own border is being invaded right now?” and “Why is Biden visiting Kyiv when he won’t even go to East Palestine?” Joe Biden supports Ukraine so they don’t; if Biden hated Ukraine, they would be its best friends. Ron DeSantis cozied up to this crowd when he called the war a territorial dispute that the US had a limited interest in. The Wall Street Journal immediately rebuked him, reminding conservative politicians that even now, pandering to a vocal minority only goes so far.

Some suggest we should cut Ukraine off to focus military resources on China. This overlooks the fact that aid to Ukraine largely doesn’t compete with aid to Taiwan since the former involves a ground war and the latter conflict would mostly be fought by air and sea. The only pieces of equipment Ukraine and Taiwan directly compete for are Stingers and Javelins. Some have suggested HIMARS can be adapted to shoot at naval targets, but the system recently performed very poorly in a test of that role in the Philippines. What Ukraine needs most are armored vehicles to help assault fortifications and protect its troops from shrapnel — since most casualties are caused by artillery, infantry fighting vehicles may be even more important than tanks.

The US has almost 7,000 Bradley fighting vehicles sitting in storage. It spends money maintaining them and plans to scrap them eventually. Bradleys can kill anything on the battlefield pretty easily and ferry a squad of infantry around while doing it, protecting them from artillery shrapnel. When the Biden administration slaps a price tag on them, ships them to Ukraine, and lets them kill Russians without Americans dying, it’s not actually spending any money. We could give a thousand Bradleys to Ukraine and not notice they were gone.

The cold hard truth the America First crowd’s simple algorithms overlook is that sending spare armor to Ukraine is a good deal for America. This is why Russia accuses the US of planning to fight it to the last Ukrainian, and why some Ukrainians suspect the US limits aid to the level that would most drain Russia. Biden’s refusals to send fighters and long-range missiles are probably more about managing escalation risk by respecting Russian red lines, but the suspicion is understandable. He’s slow-cooking Russia by escalating aid gradually.

There are more nuanced skeptics Ukraine has to contend with as well. Some fear the war may bog down into indefinite static trench warfare that accomplishes nothing but draining resources and lives on all sides — a view I’m sympathetic to, though I don’t think we’re at that stage yet. If the coming counteroffensive achieves little or its gains are quickly lost, that will suggest the front lines have become static and Ukraine will lose support. That doesn’t mean it will be cut off; it simply means it will receive only the aid necessary to prevent Russia from advancing. NATO will pressure it to go to the negotiating table and give up Crimea and part of the Donbas.

I suspect that’s how this war will end, and the remaining fighting is about seeing how far Ukraine can advance to determine how much of the Donbas it has to give up, along with the fate of Zaporizhzhia — the eventual settlement may involve Ukraine trading some of the Donbas to reclaim territory in the south. Finland had to cede 9% of its territory to the Soviet Union to end the Winter War in spite of inflicting a lopsided 5:1 casualty ratio on its larger neighbor.

Ukraine has powerful backers, but the president has shown no indication he’ll give it enough support to retake Crimea and the entire Donbas (for an alternative view, see here). It’s easy to criticize Biden, but the truth is that he’s managed the risk of nuclear and conventional escalation successfully so far. Whatever mistakes he’s made elsewhere, in Ukraine, Biden has demonstrated the value of having a steady hand at the wheel. Notice that the nuclear bluster has died out now that India and China have told Russia it'll lose its only friends if it uses nukes.

So these are the stakes of the counteroffensive: Ukraine must be able to point to significant territorial gains to justify continued offensive military aid. Its task is to grab as much as possible before its Western backers decide the war has bogged down and force it to the negotiating table. There is a vast pool of armored vehicles of all kinds available, and Ukraine can keep getting more as long as it keeps proving it can advance with them.

The Status Quo

Russia’s winter offensive has failed. It ended autumn by throwing untrained conscripts at the front lines to prevent Ukraine from extending its Kharkiv counteroffensive to Luhansk. Russia succeeded in stabilizing the front there. But to justify the cost of war and mobilization to its populace, it then attacked into the teeth of the Ukrainian defense in the dead of winter. The results were predictably disastrous.

Russia began by dashing its best units against the fortress city of Vuhledar. It made marginal gains in Luhansk, pushing the front back slightly from Svatove and Kreminna but failing to reach the strategic targets of Kupiansk and Lyman. Little happened in Zaporizhzhia, other than both sides digging in. Desperate to show its population some victory, any victory, Russia concentrated its remaining efforts on taking the small city of Bakhmut.

The amount of ink and blood spilled over Bakhmut would make you think it’s strategically significant, but nothing much hinges on it. Each side is fighting bitterly because the other wants it. For Russia, the strategic value of Bakhmut is that it gets it one step closer to the actually valuable cities of Kramatorsk and Sloviansk. But it’s not as if taking Bakhmut would put it at their doorstep; Ukraine has had all the time in the world to prepare layers of fortified lines between them and Bakhmut.

A month or so ago, when Zelensky was asked why he was spending so many lives defending Bakhmut, his answer was if Russia takes it, it’ll be one step closer to Kramatorsk. Well, yes, that’s a truism. What is actually going on is that Ukraine has been happy to whittle away Russian forces with the defender’s advantage as long as Russia has been happy to keep assaulting Bakhmut. Estimates of casualty ratios vary, with Ukraine claiming an unrealistic 7:1 at one point. 4:1 or so overall seems possible given Wagner’s human wave tactics, with the ratio more even toward the end of the battle. Pentagon officials recently claimed Russia has suffered around 20,000 dead and 80,000 wounded since January, with the lion’s share probably occurring as it fed men into the meatgrinder at Bakhmut.

Ukraine kept defending Bakhmut to make Russia keep attacking instead of digging in. As I write, it seems Russia has finally captured virtually all of the city. In the months since I’ve started commenting on the war, I’ve always said I don’t think much hinges on Bakhmut. I won’t think it matters much if Ukraine retakes it, either.

Russia’s offensive capacity is now spent. Its best tankers died in Kharkiv and Luhansk. Its best marines died at Vuhledar; its best mercenaries died at Bakhmut. Its best human shields died at Bakhmut. It squandered its elite paratroopers, the VDV, throughout the war, using them as regular infantry units to make marginal gains whenever its actual infantry failed. It used its Spetznaz as regular infantry too and now most of them are gone.

Why have Russian advances stalled? Why does it have one small city to show for the last half year of war? At this stage of the conflict, Russia’s best men are dead. Its best equipment has been destroyed. It cannot replace those units with untrained conscripts manning 70-year-old tanks. I predict that no number of mobilizations will allow it to make meaningful gains going forward. Russia will never reach the walls of Kramatorsk. It probably won’t even retake Lyman.

You might notice I’ve said nothing about the air war, which gets a disproportionate amount of media attention and is where Russia has had its greatest successes over the winter, draining Ukrainian air defense ammunition. The Iranian Shahed drones have been very efficient; it’s a win for Russia every time Ukraine uses a missile to shoot one down.

You could write an entire piece on nothing but the air war. Ukraine appears to now be shooting down nearly 100% of Russia’s missiles and drones attacking Kiev, a startling use of resources considering how low its air defense supply is said to be. It’s either being foolish or it has more than people think — didn’t those leaks say their supply was supposed to be empty by now? If it’s being stupid, we’ll know soon. It seems to be shooting down a fair number of Russian fighters and bombers lately.

We have Patriots reliably shooting down hypersonic missiles, which no one predicted — that may give China some pause — and Germany sending 15 more Gepards, the best anti-drone defense there is, as well as a large package of air defense batteries. F-16s will probably start arriving within the next few months. How will Ukraine’s supply of NATO air defense ammo fare against Russian missile and drone supplies? I’ll bet on the bigger economy winning in the end, that is, the western alliance, but I won’t give any further analysis here. Each country’s ammo supplies are a black box, a jealously guarded secret, while GDP is not.

The air war is important. But the armor supply is what will be decisive in the long run. Ukraine asks for F-16s, but what it needs is 500 Bradleys. This war is now about how much Ukraine can advance. Russia is finished as an offensive force.

Ukraine Has a Growing Advantage in Modern Equipment

The news media is obsessed with missile attacks and minor happenings in Bakhmut because that’s where the news is. You can only write so many articles about NATO’s armor supply. But that’s what matters. Some have called this a war of attrition. That might mislead you into thinking Russia’s 4:1 population advantage will be decisive. I would call it a war of attrition of trained troops and modern equipment. This is the foundation of my confidence in Ukraine’s prospects.

As the war goes on, Ukraine’s equipment gets better and more of its soldiers complete Western training. There is an essentially unlimited pool of quality IFVs and APCs available — the US alone has 4,000 Strykers I haven’t mentioned yet — and there are 2,000 Leopard 2s floating around Europe that it’s been stingy with so far. To be fair, it’s not just stinginess. NATO’s supply of modern armor is virtually infinite; the bottlenecks are in logistics and training. You have to train the mechanics, too. Now that the first wave of Ukrainians has completed training on modern equipment, the train-the-trainer model should allow the West to send more, perhaps exponentially more. I expect that hundreds more Bradleys and Strykers are coming soon.

Meanwhile, Russia’s equipment keeps getting worse. It sent many of its trainers to fight on the front lines back when it believed the war would be short. As Ukraine upgrades with Bradleys and Leopard 2s, Russia is replacing T-72s with T-54s. I believe that as the war progresses, we will enter a vicious cycle where Ukrainian veterans manning modern armor slaughter waves of Russian conscripts. The rich will get richer in experience and equipment and the poor will become poorer. The bottomless supply of NATO armor means that Ukrainian soldiers, unlike Russian ones, will get to live long enough to learn. They’ll survive artillery shrapnel.

Writing for Forbes, David Axe has an excellent series of articles documenting the progression of this war of attrition of modern equipment. To my knowledge, he is the only mainstream reporter tracking this important element of the war. One example of the equipment attrition war is night vision: Russia is running very low on modern optics to upgrade old tanks with. Ukraine will increasingly have the advantage when fighting at night. It will be increasingly able to outsee, outmaneuver, outrange, and outshoot Russia.

Below is a summary of Oryx’s list of heavy weaponry supplied to Ukraine for the counteroffensive. I’ve supplemented it with information from other sources on when pledged equipment is expected to arrive soon.

As I wrote this, Germany announced its largest aid package yet, valued at nearly $3 billion. I tried to include it, but Oryx’s list may not be fully updated; the artillery doesn’t seem to be reflected yet. The pledge of 20 more Marders, 30 Leopard 1s, and a hundred unnamed armored vehicles (not included in the list above) suggests this may be the beginning of the second wave of armor I expect, now that Ukraine can use some of its trained troops to train others. Word is that France is planning to send another tranche of AMX-10s too, basically light tanks. My training-bottleneck theory will be substantially falsified if the US fails to send more Bradleys or Strykers within the next couple months.

Potential Targets

“He who defends everything defends nothing.” As analysts speculate about where Ukraine’s hardest blows will fall, I keep remembering that famous quote from Frederick the Great. Right now, Ukraine is trying to make Russia think it could attack anywhere to make it try to defend everywhere. In the end, I think Ukraine should and will attack whichever place Russia chooses not to defend. I have an idea of where that might be. But I’ll describe other potential targets and the pros and cons of attacking them first, beginning with the most valuable.

To the sea

Strategically, the biggest prize would be for Ukraine to cut a path through Zaporizhzhia oblast all the way to the Sea of Azov. It hardly matters where. It’s not about taking cities like Melitopol or Mariupol. It’s about cutting Russian-occupied territory in two and winning Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, and Crimea without fighting for them.

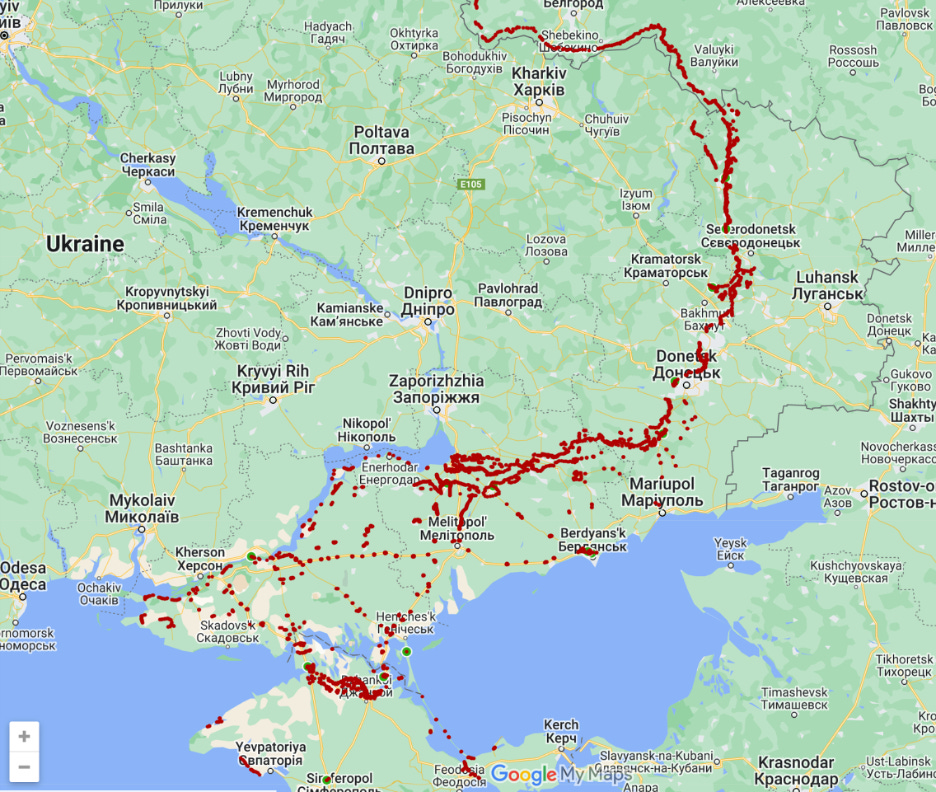

If Ukraine managed to create and hold a corridor to the sea anywhere between the blue lines I’ve drawn, it would be a major coup. It would cut off Russia’s major supply lines to all territories to the west, limiting it to only what it could get through the Kerch Bridge, circled. Notably, the UK recently gave Ukraine Storm Shadow cruise missiles, which have the range and punch necessary to threaten the Kerch Bridge even from Ukraine’s existing positions. If Ukraine drives to the sea, Russia will probably lose both major supply lines to the west. It would lose its remaining holdings in Kherson, Zaporizhzhia, and Crimea without a fight. Disaster.

Of course, Russia knows this, which is why it spent all winter constructing multiple lines of defense in Zaporizhzhia. It may also be why this is one of the few regions it didn’t launch any attacks in; its troops there are the least bloodied.

The area to the north of Melitopol is a maze of fortifications. A couple other points are interesting. First, Russia has heavily fortified Crimea, too; it’s not clear to me why, since it would take Ukraine a long time to even reach it. As you can see, in the entire region of greatest danger Russia has fortified strong points along the highways in case Ukraine breaks through the front lines — note that it hasn’t done this in Donetsk or Luhansk. It has a cluster of defensive positions protecting its final fallback at the port city of Berdyansk, its regional headquarters. The Russian fleet can transport a limited amount of personnel and equipment back and forth from that port.

Russia is prepared to defend against a Ukrainian drive to the sea. This is why I think Ukraine won’t focus its efforts there. It may launch feints to keep Russia spending resources; it may even launch a big assault just to see if it can get lucky and break through. But if Russia commits appropriate resources to defend the south, as I expect it will, I doubt Ukraine will commit to a drawn-out slugfest attempting to force its way to the sea. It would be far too bloody and have no guarantee of success — exactly the conditions that might convince Ukraine’s backers to cut down on offensive aid.

The strategic prize in the south is far too risky. War is the continuation of politics by other means, and politics demands that Ukraine reclaim maximum territory with minimum losses. If I were Ukraine, I would continue to threaten Zaporizhzhia and Crimea to draw as many Russian resources there as possible and I would take out the Kerch Bridge to make the threat more credible and make it more difficult for Russia to supply the entire southern region. But I would not launch a counteroffensive in the south.

That brings me to happenings in Kherson.

Across the river

There have been rumors of Ukrainian footholds on the east bank of the Dnipro River for weeks now. Let’s cut to the chase: no, Ukraine doesn’t control any real territory there, nor is there much territory worth controlling. It’s a bunch of swampland. Ukraine may have recaptured a few islands in the delta that its commandos use as launching points for raids, joined by partisans sabotaging Russia behind its front lines.

This area is probably the least valuable of all the regions Ukraine might assault. Its value is instrumental to other objectives. First, if Ukraine launched a large attack across the river, it would hope to control the canal delivering water to Crimea from the reservoir at Nova Kakhovka, roughly outlined in blue. From there, it would hope to advance toward Crimea. This would very likely be intended as a secondary effort supplementing an advance toward Crimea from the Zaporizhzhia direction through Melitopol.

Again, Russia is perfectly aware of this danger; it’s built a series of strong points along all the highways from Kherson oblast to Crimea. I strongly suspect that Ukraine has achieved its real objective simply by getting Russia to spend time and resources fortifying this region. This is the westernmost area of the front and any troops either side sends here will be stranded far from wherever the actual fighting takes place. Ukraine is harassing the area to get Russia to divert as many men there as possible. Russia has to respect the threat; if it doesn’t defend against it, Ukraine may decide to take the opportunity to advance.

The bigger picture this fits into is that Ukraine has the benefit of short interior lines versus Russia’s longer exterior lines. Simply put, Ukrainian troops travel a shorter distance, and therefore quicker, whenever transferring between Kherson/Zaporizhzhia and Donetsk/Luhansk. It also now has higher-quality armored vehicles, potentially with better coordination. In the coming counteroffensive look for Ukraine to try to play ping-pong with the Russian army, attacking in one area to get Russia to divert forces there, then using its shorter interior lines to suddenly shift to the true target somewhere far away. Interior lines plus more maneuverable units are the force multipliers Ukraine will try to exploit to the fullest. Where will Ukraine attack? I predict this much: whatever it attacks first will probably not be its main target.

Encircling Bakhmut

It pains me to discuss Bakhmut. I don’t want to encourage the belief that the war hinges on it. But the city has some degree of importance simply because both sides have fought for it, as basically a random patch of ground they’ve agreed to duel on. Things have the value we assign to them, I guess.

It appears very likely that Russia has taken all of Bakhmut, in spite of Ukrainian denials. It is a sign of the myopic fixation on Bakhmut that people debate whether Ukraine still holds a few streets as if the question matters in the slightest. For a good take on the Pyrrhic nature of Russia’s victory, read this assessment from Igor Girkin, former commander of the DPR’s forces. I learn a lot from following his commentary and Russian media, especially Vladimir Solovyov’s show. Russian media has consistently become more pessimistic over the course of the war. Julia Davis is invaluable for her daily translations of Russian talk shows.

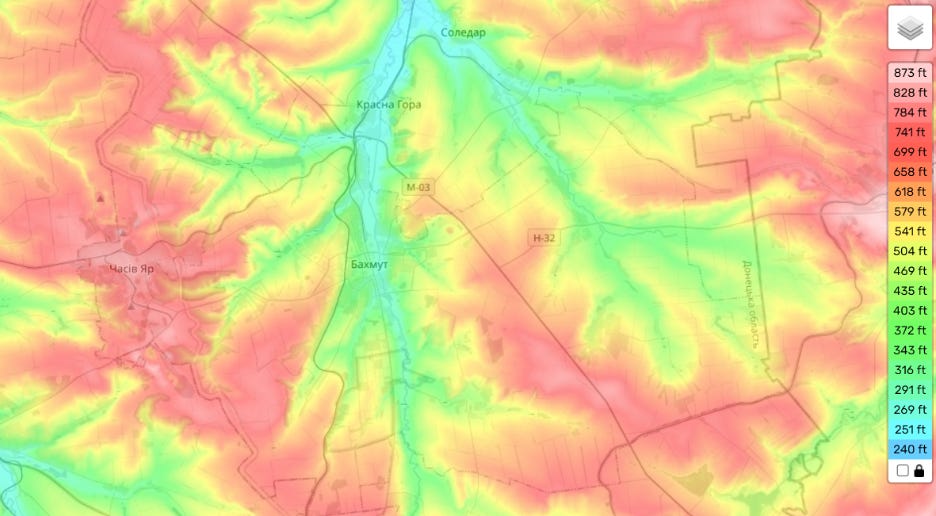

Zelensky would have people believe that Bakhmut is some geographic natural fortress that serves as the lynchpin of the Donbas; he said as much when justifying Ukraine’s continued defense. Interestingly, nothing could be further from the truth. Bakhmut sits at the bottom of a valley.

Remember when things got particularly dicey for Ukraine a couple months ago and it was nearly encircled in Bakhmut? Russia had seized the high ground to the north and south and surrounded it on three sides, shelling it from above. The two sides now appear to be trading territory.

Ukraine has captured around 20 square kilometers on the northern and southern flanks of Bakhmut. Some reports indicate that Russia withdrew Wagner and VDV units from the flanks to complete taking the city proper and replaced them with poorly-trained regular units that ran when Ukraine attacked. Ukraine now possesses positions on the high ground flanking Bakhmut, allowing it to be the one who shells Russia.

One of its top generals is now claiming that Ukraine is close to tactically encircling Bakhmut, basically meaning surrounding it on three sides. I don’t see evidence of that yet. But what interests me about the exaggeration is that it suggests Ukraine really wants Russia to send reinforcements to Bakhmut. It seems likely that in the near-term Ukraine will attempt to continue its gains on the high ground surrounding Bakhmut, drawing more Russians there to continue the battle of attrition, but this time with the terrain on its side. Because Bakhmut is its winter offensive’s big prize, Russia may be forced to commit troops there assaulting the high ground, diverting them from wherever Ukraine actually wants to attack.

And where might that be? I don’t know, but I do have a good target in mind.

Why Luhansk makes sense

Why attack Luhansk? Because, as Fredrick the Great would understand, that is what Russia has chosen not to defend. Unlike Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, it has only a single line of fortifications, behind the key city of Svatove, and it has no fallback positions behind it. The highways are empty. Many of its units there are still battered from Ukraine’s Kharkiv counteroffensive and winter fighting. The once-elite 1st Guards Tank Army on duty in Luhansk has been decimated twice now, first in Kyiv, then in Kharkiv.

If Ukraine punches through the single line of defense in Luhansk somewhere in the Svatove region, it’s hard to say what would stop it. It could potentially get all the way to the supply hub at Starobilsk pretty quickly, maybe even take it. Most of the northern half of Luhansk oblast would be at risk. It could swing south and surround Severodonetsk without dealing with the mass of fortifications there. There are a lot of options if Ukraine breaks through the single line around Svatove, manned by troops it’s already beaten and battered.

The approach I have in mind, breaching Russia’s defenses and then blitzing through northern Luhansk, would be an ideal task for Ukraine’s newly-armed elite 82nd Air Assault Brigade. Curiously, it has all 14 heavily armored Challenger 2 tanks, perfect for creating a breach, and all 90 fast Stryker APCs, perfect for exploiting one. It also has all 40 Marder IFVs—one interesting thing about the choice of the Marder rather than the Bradley is that the Marder is faster. The 82nd would be the perfect unit to spearhead a breakthrough of the front line and then run wild in Luhansk.

Russia has good reasons for not defending Luhansk as heavily as other places; it can’t defend everywhere equally, and the greatest risk is in the south. Northern Luhansk is no great strategic prize compared to Zaporizhzhia or Crimea, and lacks the symbolic importance Bakhmut has acquired. It’s also sparsely populated.

What northern Luhansk offers Ukraine is the chance for a relatively easy win early on, one that would offer a lot of territorial gain for a relatively minimal loss of lives. War is politics, this war more than most, and the scoreboard us idiot Americans look at to determine continued military aid cares more about quantity of territory acquired than the strategic value of it. We are not informed enough to care that Luhansk isn’t as valuable as Zaporizhzhia.

Besides, that territory does have value in a few ways. Operationally, Ukraine can move south to flank and surround fortified Donbas cities like Severodonetsk and Popasna. Politically, taking Luhansk has been one of Russia’s main goals from day 1 of the war. It would regret losing it. If Ukraine breaks through and runs rampant with relatively few fast mechanized brigades, Russia may panic and overcommit troops from elsewhere to stem the bleeding. That would open the door for Ukraine to reverse course using its shorter interior lines and launch a bigger attack elsewhere, somewhere it values more.

Maybe Ukraine will do something completely different. Probably it will. It has many options, along with the flexibility to switch course at any moment. In the end, Ukraine will likely attack wherever Russia has chosen not to defend.

Pretty bold. Lot of bloviating with little actual technical analysis. I made a note to return to this in 4 months. I strongly suspect you will be proven incorrect.

the longer this absurd conflict goes on the greater the chance of direct US/NATO involvement, which would be a catastrophe.