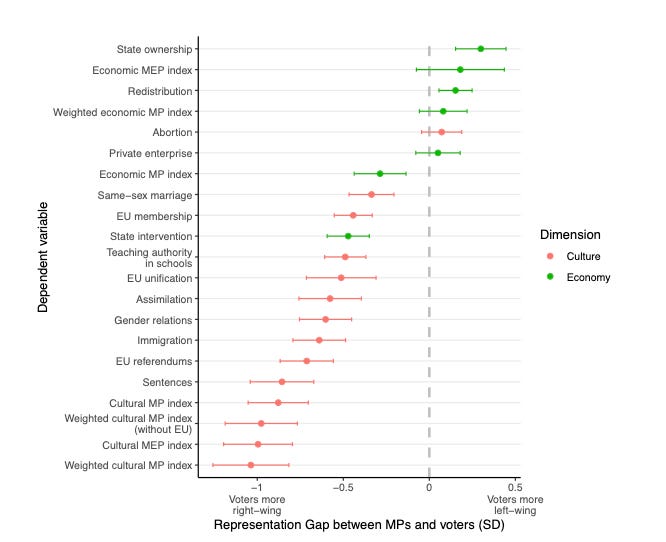

Laurenz Guenther (X, website) is a Research Fellow at the Toulouse School of Economics. He joins the podcast to discuss his working paper, “Political Representation Gaps and Populism.” Relying on survey data of politicians and regular citizens across the EU, he finds a simple explanation for the rise of populism across the continent. Politicians are one standard deviation to the left of the public on social issues. As Guenther points out, the gap is larger than the difference between the typical communist and conservative MP. Immigrants are more conservative on migration and assimilation issues than politicians. These are quite remarkable findings, and must be factored into any understanding of contemporary European politics.

Beginning in the 2010s, the salience of the immigration issue took off. Voters have been flocking to populist candidates as a result ever since. As much as many academics and political leaders would like to deny this fact, this provides the most straightforward explanation for recent trends.

The conversation focuses on what to make of the data. Does this mean that to defeat populism, all politicians have to do is become more restrictionist? How does this square with the rise of populism being a global phenomenon, even in countries where immigration isn’t an issue? What to make of research showing that populism is bad for the economy? Are there examples of European parties that have headed off the rise of populism in this way? Guenther discusses the well-known case of Denmark, but also brings up the surprising example of Hungary, where Orbán took the mainstream conservative party, made it more populist, and has dominated the politics of his nation ever since.

Another perhaps surprising finding is that there is much less of an elite-public gap on economic issues. If anything, politicians are more inclined to support free markets. Hanania asks whether the gap might be even greater than the paper suggests, given the way questions are framed. This helps explain why left-wing populism hasn’t been as successful as its right-wing equivalent, whether in the US or Europe.

Abortion pops up as the one social issue on which there is no notable difference between elites and the public. This is reminiscent of experiences in American red states, where politicians take abortion rights away while voters nearly everywhere support the pro-choice position in referendums. The conversation discusses why this might be.

The rise of right-wing populism is the political story of our time. By grounding the discussion in empirical data, Guenther sheds light on why mainstream parties have struggled to respond, and what strategies may or may not work to blunt the populist surge. This conversation helps provide a clear and evidence-based perspective on one of the defining issues of our era, while providing hints of possible future productive avenues of research.